JUMP CUT

A

REVIEW OF CONTEMPORARY MEDIA

![]()

Farm family dinner before electrification: an oil lamp on the table. Power and the Land uses a classic before and after comparison the show modernization by rural electrification.

Al Gore lectures on global warming in An Inconvenient Truth.

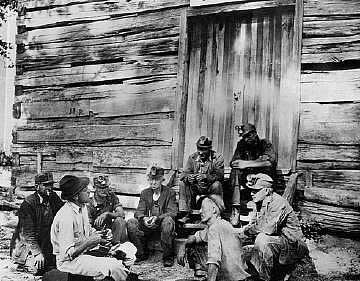

Miners in People of the Cumberland. The film centers on ordinary people in the middle of the Great Depression.

Wiseman’s Titicut Follies presents a sometimes surreal picture of mental hospital incarceration.

Attica depicts a prison uprising and its aftermath.

Underground uses complex mirror shots to interview the Weather Underground and protect their identities while fugitives.

Spike Lee on location for his HBO documentary When The Levees Broke.

Pink Saris (2010), directed by Kim Longinotto, follows a women's "gang" in northern India that helps untouchable-caste women fight violence.

Documentary:

intelligence and/or emotion?

reviewed by Chuck Kleinhans

Jonathan Kahana, Intelligence Work: The Politics of American Documentary (New York: Columbia University Press, 2008).

Belinda Smaill, The Documentary: Politics, Emotion, Culture (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010)

Over the past two decades documentary studies vastly expanded. Both in the scope of topics covered and the range of examples studied, analysts moved beyond the traditional restriction to the social documentary tradition to cover everything from early cinema actualities to contemporary digital social media, home movies to artist autobiography, reality TV to professional dramatic re-enactment of documents. The annual Visible Evidence conference, a peripatetic and now international event without an official organization, and the same-named book series from the University of Minnesota Press give substance to the field. While studies of dramatic narrative features seem to face new crises—will theatrical exhibition evaporate? can familiar aesthetics work when people see movies on tiny portable devices?—work on documentary seems to thrive on ferment and change. In this context, two new books add to the richness of the field. Intelligence Work: The Politics of American Documentary reworks a familiar terrain with a new set of perspectives while The Documentary: Politics, Emotion, Culture brings matters of affect to the fore in reassessing the mode from an international perspective.

Jonathan Kahana aims to present a large analysis of the U.S. social documentary tradition by stressing its communicative function of conveying “fragments of social reality from one place or one group or one time to another” and delivering them in an articulated form that engages the receiver’s imagination. Thus his specific film analysis tends to examine rhetorical expression using “metaphor, analogy, allegory, and generalization.” (p. 2). The author makes an unexpected but welcome turn to the Post WW1 active talk of the media and the public sphere by Walter Lippman, John Dewey, and others concerned with the nature of public opinion in a democracy, a discussion that influenced John Grierson and others who saw audiovisual media as a potent new tool. Kahana gains a certain purchase on the question of a political cinema by referring to these larger issues of democratic communication, although it is not a fixed yardstick for him. In contrast, Belinda Smaill quickly dismisses Griersonian realist documentary practice as at best reformist and moves on to more provocative contemporary examples. Both writers pay ample attention to works that operate in a critical or counter-tradition to the mainstream.

Using historical progression to organize his selections, Kahana examines works that operate in key phases of US documentary history. He begins with the New Deal by presenting both the officially sponsored films (e.g. Joris Ivens’ Power and the Land, 1940) and the activist alternative (Sidney Meyer and Jay Leyda’s People of the Cumberland, 1938). A large leap takes us to the New Left with attention to films on prison (Cinda Firestone’s Attica, 1973) and the SDS Weatherman faction (de Antonio’s Underground, 1976). In a concluding section, films that concentrate on the Presidency (Pierce Rafferty and James Ridgeway’s Feed, 1992) and some experimental artist generated works give a counter balance. The study only tangentially discusses some of the most visible grassroots US political movements of the past 50 years such as civil rights, the antiwar and student movement, race and ethnic organizing, and the feminist and queer movements and particular campaigns such as against the two Gulf Wars, anti-corporate strategies, and the critique of the post 9/11 War on Terrorism. After the New Deal examples, for Kahana the main concern concentrates on the films’ forms and expressive rhetorical organization, not on actual connections to social and political movements for change.

To be fair to Kahana’s argument, he rather acutely and cleverly disposes of a whole swath of recent high profile documentaries in a quick and decisive look at An Inconvenient Truth (Davis Guggenheim, 2006), pointing at its operation with Al Gore as onscreen expert. Kahana sees the film’s “intertext” as “the spate of recent documentary portraits of well-known progressive intellectuals, such as Noam Chomsky, Jacques Derrida, Edward Saïd, Howard Zinn, and the monotonous parade of talking heads marshaled by producer-director Robert Greenwald” (director of Wal-Mart: The High Cost of Low Price, 2005, and Outfoxed: Rupert Murdoch’s War on Journalism, 2004). Noting “the family resemblance between Gore’s character in the film and the strategic stupidity of the protagonists played by Michael Moore, Morgan Spurlock (in Super Size Me [2004]), and Sasha Baron Cohan," Kahana describes them all as “village idiot” characters who have worn out the shtick for this kind of political criticism. (p.32)

In contrast, Smaill is much more indulgent to such irony and accepts its subversive potential in critiques of corporate capitalism such as The Corporation (Mark Achbar and Jennifer Abbott, 2003), Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room (Alex Gibney, 2005), and Super Size Me. She sees the strategies operating here as Socratic, and motivated by a kind of “civic love” concerned with the social collective and good citizenship. Throughout the study, she is drawn to expressive emotional examples: the representation of children in Born Into Brothels (Zana Briski and Ross Kaufmann, 2004), the audience investment in aspirant hopes and fears in Australian Idol reality competition (2003-2009), “the spectacle of anguish and suffering” in the victim documentary (Fix: The Story of an Addicted City (Nettie Wild, 2002) on Vancouver BC drug addicts; Rize (David Lachappelle, 2005) on Los Angeles African American krumping subculture), and the sensation of depicted female desire in several documentaries about pornography. She also considers the issue of gendered pain used by British maker Kim Longinetto (e.g., The Day I Will Never Forget, 2002,on female genital mutilation in Kenya) and multiple layers of loss in several documentaries on Asian Australian subjects. Smaill’s approach welcomes the personal story, the autobiographical essay, the witnessing victim report: not as an end in itself (and thus an exercise in empathy and/or offense for the audience) but as the individual tale connects to a social and civic learning.

At his best, Kahana gives convincing arguments for seeing the rhetoric of certain specific films (and their neighboring types) as a key to understanding their effectiveness, such as the deep seeded allegory of Power and the Land that rural electrification in the practical sense stands for the weaving together of the national social fabric. Repeatedly, Smaill tends to focus on the case that allows the audience to form a sympathetic engagement as a starting point to a richer analysis. One example: Smaill spots almost latent connections in specific cases such as the marketization of ethnic identity in a way which subtracts cultural critique and political contestation in Australian Idol and which gives us new tools for looking at other texts. She also does so in a clear and concise style that encourages readers to build on her start.

Kahana is often intensely insightful about form and style in the films he considers, such as a sophisticated analysis of sound particularly in radical documentaries of the 60s on. He also maintains a challenging mix of works as when in discussing films about prison and prisoners as connected to changes in national understanding of incarceration in the 70s. He discusses both Attica, on the landmark prison rebellion, and Titicut Follies, 1967, Frederick Wiseman’s study of a Massachusetts state mental institution. But he has little patience for considering actual political efficacy in his surveys. Because Baghdad ER (Jon Alpert and Matthew O’Neill , 2006), shows battlefield injuries too disturbing for broadcast or basic cable, it was booked on HBO. Kahana dismisses it as “pornographic” and just part of the “exploitation” mix of HBOs documentary lineup. Similarly, Spike Lee’s HBO mini-series investigation of Hurricane Katrina, When the Levees Broke (2006) is downgraded in favor of an arty ten-minute long miniature work, South of Ten (Liza Johnson, 2006) which had virtually no circulation. Kahana seems to believe there is an either/or choice to be made here. In contrast, Smaill’s imagination seems to allow for documentaries as versatile and adaptable to different cases, audiences, and moments of political flux.

Underground is extolled by Kahana as “a formal primer on the strategies of anti-imperialist politics and their incorporation into film making and other intellectual forms.” (204) Certainly the film is formally complex, and thus interesting to study for its construction, but what of the Weather Underground? What were its politics? At the time of their initial formation, during their outlaw phase, and in retrospect they seem a spectacular failure. Kahana writes about political documentaries, but doesn’t seem clear about what politics are: in the films, in the audience, in relation to social movements, in distribution and exhibition. For example, he makes the astonishing claim that Jill Godmilow is “the exemplary auteur of American political documentary” on the basis of What Farocki Taught, 1998, a shot-by-shot remake of a cerebral German filmmaker’s self-reflexive case against napalm in Vietnam from 30 years earlier. Godmilow offered it as a pedagogical object lesson for filmmaking students. Kahana cheers for the “critical force of this gesture (which) lies in its exposure and display of confusion.” (345) How this contributes to progress in the body politic is not examined.

In sharp contrast, Smaill’s excellence lies in knowing what she’s doing: examining how emotion is both represented and evoked in and by documentary for political ends. This fluid conception of politics is deeply imbricated with feminist and other movement politics that assume affect is part of political motion, something that incorporates the agenda of change. That movement might be uncertain, in need of constant correction, but it is also affirmative and embodied, in the maker, in the film, and in the audience and the social world.

********

Note: Film Quarterly originally commissioned this review. Submitted in November 2010, it was accepted by the FQ book review editor and sent on to the editor and editorial board. In January 2011 the editor, Rob White, told me the article was accepted by the board and that a copyedit would be sent later. No mention of any problems with the article as it stood. Normally a copyedit at this stage is just a cosmetic conforming to the publication’s style sheet. Normally editors notify writers of any suggested or required revisions at the point of acceptance, and the writer then takes the initiative to do any rewriting. Six months later, in July White sent a heavily rewritten copy back and gave me three and one-half days to accept his massive change. I found he had altered my meaning, coarsened my argument, cut a key paragraph, and inserted trite and inflammatory terms such as “terrorist.” I offered to do a close style edit taking into account his changes and return it immediately to be run without further editorial alterations by him, but said I would not accept changes of content and substance. He wouldn’t agree and I withdrew the review.

Most absurdly, White added this to his rewrite: [This suggested rewrite reflects the fact that the original conclusion reads as if FQ were publication with an activist/movement position.] I’m sure no one has ever mistaken Film Quarterly for an activist or movement publication. The reader can decide if my conclusion reads as White feared it did.

To

top![]() Print

version

Print

version![]() JC 53

JC 53 ![]() Jump

Cut home

Jump

Cut home

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License.