JUMP CUT

A

REVIEW OF CONTEMPORARY MEDIA

![]()

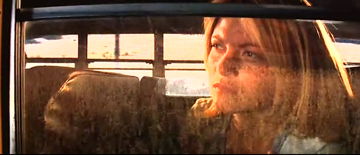

In this frame, the students peer out the windows as if their bus is a fortress that will protect them from the outside dangers. Ironically, the bus serves as their ‘Terrible Place’, which will trap the selected victims to be picked off one-by-one.

The Final Girl Minxie in Jeepers Creepers 2 can only come to understand the Creepers intentions through two dream sequences: the first, which acts as a premonition to their impending situation; and the second, which details what the Creeper is after. She is arguably never the Creeper’s ultimate victim; rather, she is a mere nuisance to his desires.

Minxie’s premonitions reinforce the dire situation of being both stranded and under attack, suggested through her peering out the window of the bus and her encounters with dead males she has never met.

Darry Jenner from Jeepers Creepers (2001) appears to Minxie, warning her to turn around and travel no further.

Similarly, the Creeper’s initial victim Billy Taggart in Jeepers Creepers 2 warns Minxie to avoid the field and turn around. Darry and Billy represent the age range of acceptable victims (people of desire), ranging from barely pubescent to virile, young adult males.

Darry demonstrates to Minxie in her second dream sequence what the Creeper intends for his victims, by presenting himself to her once the Creeper has taken the body part he desires.

While the characters are comprised primarily of male, high school basketball players, there are a few, feminine female characters present, none of whom die by the hands of the Creeper.

The male characters show a range of diversity racially, but physically are well-built, attractive individuals. However, there are present alpha males and ones, who are not the controlling, domineering kind.

This divisive categorisation and subjugation recall the racial prejudice of the 50s and 60s, demonstrated through the argument between the white and the African American segment of the team.

The vitriol displayed on the teammates face further emphasizes the racial tensions, heightened by the impending danger. Moreover, these racial tensions are suggestive of the prejudices and tensions accorded to the LGBT community presently.

Finally, the Creeper’s days are up and his visibility must end. As suggested through the opening sequences, he will return the next 23rd spring for 23 days. This image, however, recalls the lynching in the southern states as they too were commonly used as deterrents for African Americans.

Conversely, the image of the old white man sitting with a weapon similar in size and shape to a shotgun illustrates society’s unwillingness to let change occur and allow for visibility in civilized society, rather than on the periphery. The strung up image of the Creeper and the old man depict that conservativism towards, in this case, homosexuality.

Representations of desire: killer as queer

As the Creeper in Jeepers Creepers 2 decidedly picks off his victims, one by one, those victims’ body parts become subject to the Creeper’s desires. Desire, in this case, functions as a restorative property for the Creeper. He therefore selects his victims based on the most desirable body part (i.e. – the head, the eyes, the hands, etc…) in a process that can only be described as “sniffing out” or “smelling” the desired thing. This occurs because he must harvest these body parts for his 23 years hibernation and also replace parts of himself that are destroyed by his victims. The Creeper is then what Harry Benshoff defines as the “monster queer”: a monstrosity that accounts for the sexual Other, oft disrupting heteronormative romance or intentions. As the monster queer disrupts heteronormative romance, he too disrupts heteronormative narratives: the central fragmentation present in the slasher film, further evinced in the fractured body, as the Creeper selects this part or that.[21] [open endnotes in new window]

|

|

| One of the students becomes an unwitting victim in the ‘Terrible Place’, losing his head to the Creeper, which the Creeper uses to regenerate himself. | The Creeper, rightly named, has sharp, unnatural features. His teeth are bountiful and malicious, while his skin is sleek and demonic. |

As the majority of these victims are men, it appears he is looking to select the most attractive portion of that victim’s body to better equip himself. Attractiveness is evident in his selection, because each victim adheres to a specific body type and specific appearance—comparable to what conventional standards defines as attractive. It is therefore suggested that the Creeper selects these victims based on his apparent attraction or “desire” for these male characters. Consequently, the Creeper aspires to be a more attractive form, in spite of his inability to mutate his physical appearance indefinitely – each time he adds a victims’ appendage, the appendage is recognizable as the victim’s for mere moments and then the monster restores back to his original self.

Physical desire and reconstituting one’s self as desirable seem to be the Creeper’s intention; and more importantly, that intention is centred onto masculinized victims. In other words, the Creeper is regenerating himself in order to attract potential same-sex sexual partners. Clover previously established that the victims in these films were often portrayed as feminized during their moments of demise. Her initial assumptions regarding the ostensibly masculine slasher, who desired the female victim and disposed of the male would, suggest that a renegotiation of the slasher’s desire is in order. Clover argues the point

“that violence and sex are not concomitants but alternatives, the one as much a substitute for and a prelude to the other as the teenage horror film is a substitute for and a prelude to the ‘adult’ film.’”[22]

Consequently, if the desire for these men is self-indulgent, as it seemingly is for the Creeper, he awaits the perfect “mate” or “partner” and will utilize these victims as identities he decides will better his body. Not using the victims solely for a sexual engagement, he will use violence to satisfy that need.

Identity and gender constructs play an integral role in heteronormative society, as displayed through the characters on the bus: an all male basketball team accompanied by extremely delicate, feminine cheerleaders. Heteronormativity, as defined in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Queer Psychology: An Introduction, refers to “the perceived reinforcement of certain beliefs about sexuality within social institutions and policies.”[23] Inherent in these “beliefs about sexuality” are the implications that sexual preference should be heterosexually influenced, that a “family” constitutes a heterosexual coupling, and that marriage is limited to one man and one woman. The film’s characters epitomize this definition of heteronormativity, as they build the foundation for the film and for the types of victims the Creeper chooses. Each male victim displays prominent attractive features and represent the varying masculine identities typically encountered in a U.S. high school. Generally, such students might find homosexuality unnatural or monstrous, often bullying or provoking a queer student. Benshoff supports this claim, arguing:

“certain sectors of the population still relate homosexuality to bestiality, incest, necrophilia, sadomaschism, etc. - the very stuff of classical Hollywood monster movies. The Concepts ‘monster’ and ‘homosexual’ share many of the same semantic charges and arouse many of the same fears about sex and death.”[24]

This irrational fear regarding the “monster” and the “homosexual” works to create a disingenuous identity formation, which propagates further fear and misunderstanding of queer identity. In other words, the monster is just as feared as the homosexual; and queer identity, because of its apparent monstrosity, becomes an identity construct to mistrust.

Just as the Creeper displays extreme monstrosity, his victims display a similar monstrosity as their ostensible masculinity battles the Creeper’s sexually violent advances. In these instances, the characters label the victims as the Creeper’s choice, instigating a verbal argument between the trapped boys divisively deciding to kick those he selects off the bus. These singular moments in the film occur as the male victims are trapped in their Terrible Place, with the Creeper looking in at them erotically through the bus’s many windows. Desire is at the forefront of this voyeurism, recalling Laura Mulvey’s psychoanalytic concept of the male gaze:

“In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female. The determining male gaze projects its phantasy on to the female figure which is styled accordingly.”[25]

While the Creeper does not project his “phantasy on to the female figure,” he projects that desire onto the male form, taking in the men’s attractive qualities, desiring those qualities overtly and lasciviously. It is thus arguable that in this film a queer gaze has been appropriated, whereby a symbolic order remains intact, but the film renegotiates the traditional gender binary from male/female to male/male. The receiving male is sized up by the camera/the Creeper, emphasizing (a) the character’s sexual magnitude and (b) his inferiority to the camera’s/the Creeper’s gaze. This new queer gaze reflects those same controlling properties and overt, bodily exploitations Mulvey detailed in her theory of the male gaze.

Among the men trapped in the bus, they too recognize this form of desire evinced by the Creeper’s sniffing, smirking, toothy-grins and the erotic licking of the bus’s rear-facing window. The rear window is situated within the back door, ironically labelled Emergency Exit. “Back door” is a common euphemism for “buttocks” or “anus”; however, it is even more suggestive of anal intercourse. With the monster queer peering in through this “back door,” going so far as to lick it, it would suggest that what the Creeper desires is the penetrative areas of the male body: the anus, the mouth, and even the eyes. The camera accentuates these actions using multiple shot reverse-shots to highlight the victims’ reaction to the Creeper’s highly suggestive, lascivious advances. Consequently, the Creeper’s gaze penetrates the bus, evincing his queernes to the passive males within.

His recurring gaze that accentuates his queerness coupled with the act of choosing help to establish the underlying cathexis exhibited by the Creeper’s projected desire. In other words, it is his libidinal energy focused onto that male form that shapes the Creeper’s determined gaze. These men are unaccustomed to the voyeurism directed onto themselves, as they, arguably and suggestively, direct their gaze onto the female form. It is this shift from active/male to passive/male that propagates further a queer interpretation of the monster and his victims. Moreover, it also provides an instance for the homosexual to renegotiate those power structures related to gender that are constituted and rooted in the patriarchal foundations of Western Society.

Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick argues in Epistemology of the Closet that as we as humans further subcategorize ourselves into those rigid, restrictive binarisms (hetero/homosexual), we further divide ourselves apart from one another.[26] While she emphasizes the hetero/homosexual binary predicament, she does not focus on any truth labelled out by those subscribing to the “minoritizing” or “universalizing” views of sexuality as she deems their “truths” arbitrary. Rather, her emphasis is on the performative nature associated with minoritizing and universalizing views. In other words, those who view homosexuality and its problems as relevant only to a small set of individuals (minoritizing) would be more inclined to perform homophobic, divisive actions. Thus, this division emphasize how devaluation underpins the monstrosity of the Creeper, because he must exist in a period of “every 23rd spring for 23 days” when he gets to eat.[27] He can only exist in this period of growth and rebirth (suggested by “spring”) for a miniscule amount of time, because the construction of his queer identity is contrary to the heteronormative ideal of male desiring female and vice versa.[28]

|

|

| These boys are representative of the ideal, adolescent male prevalent in Jeepers Creepers 2. There is very little variation among the characters in terms of sexual appeal. Each boy would represent a facet of the male population deemed attractive. | The Creeper ‘sniffs out’ what he desires in his victims. In this shot, we see the Creeper’s nostrils flaring out as he determines which character(s) will provide him with the most suitable body parts. |

|

|

| Once the Creeper discovers a feature he so desires in a victim, he makes facial and bodily gestures to inform the victim of his choice. | During the Creeper’s regenerations, the victims body parts the he takes can be made out as they attach and/or regenerate any wounds the Creeper suffers. In this case, the decapitated boy’s head restores the Creeper’s damaged one. |

|

|

| The Creeper selects the best feature of his victims in order to better himself. Because he is unable to attain these objects of desire for sexual activity, it is arguable that he takes their best features to recreate the ideal male form for himself. | The Creeper erotically licks the glass on the emergency exit door attached to the back of the bus. This frame demonstrates the overt sexual nature of the scene as the victims are objects of desire; but, also, shows how sexual advances can be used to torment victims further. Moreover, licking the back of the bus is suggestive of licking the penetrative areas of his victims. |

Furthermore, his limited active existence provides him with a fragmented population, from which he can select his victims. It is a notion suggestive of the queer community, whereby queer identity is ostracized to the outskirts of heteronormative society. And where their identity constructs are limited, they too have limited partner choices. Similar to that ostracizing, the Creeper must exist outside the cities and towns of modern United States, isolated to the largely unoccupied frontiers of the Midwest. Vast open fields and extensive road provide the setting for Jeepers Creepers 2, trapping the victims in the bus within this queer terrain dominated by the Creeper. Though his visibility is obvious to the viewer during periods of sunlight, the victims do not encounter the monster queer until nightfall; only the young boy at the onset of the film encounters the Creeper and meets his demise during the day. Here the film depicts its manifold representations of queer monstrosity, which

“manages to equate or conflate homosexuality with most…horror film signifiers of depravity: all manner of sex perversion (bestiality, necrophilia, pedophilia), as well as human sacrifice, Satanism, rape, and serial killing.”[29]

Underlying the Creeper’s model for selection is the representation of paedophiliac desire and bodily rape, suggested by the younger, on the fringes of barely pubescent, boy and the bus’ array of men. Furthermore, Satanism is evoked in that the monster queer looks devilish (i.e. – sharp features, sharp teeth, sharp piercing eyes and a demonic aura), suggestive of a supernatural being, a demonic figure. This link between archaic assumptions regarding queer identity as monstrous with the victimization of men epitomizes the monster’s assumed identity formation as queer. In addition, it provokes the specific religious ideology regarding homosexuality and queer identity, where homosexuals are doomed sinners, separated from heaven and ostracized to hell.

Given that the Creeper escapes the fringes of hell and with agency unwittingly consumes his male victims, Christian ideology and Judeo-Christian Western society are placed at odds against an indestructible force. Where the monster queer is indestructible (he is stabbed multiple times in his body and his face), he becomes a force that Western society cannot overcome. Just like the pleasures Christianized Western societies cannot overcome, the monster queer represents that part of queer identity that accepts his/her sexuality and does not shirk the desires for the [same-sex] body. Sedgwick notes:

“Christian tradition…had tended both to condense ‘the flesh’ (insofar as it represented or incorporated pleasure) as the female body and to surround its attractiveness with an aura of maximum anxiety and prohibition.”[30]

Whereas these traditions elaborated the female form as an indicator of pleasure (or the flesh), queer identity labels as the indicator of pleasure the same-sex body. Queer identity constructs, therefore, go against heteronormative ideals to fetishize the opposite sex, but also disregard any sense of maximum anxiety or prohibition of desire. Moreover, as the Creeper consumes his victims’ body parts, he is in turn giving in to the flesh, but he is also working to recreate his own form into that idealized male figure.

The Final Girl (Minxie) works to combat the Creeper’s intention to turn her male friends into a piece of himself, fighting back violently and forcefully. Her position in Jeepers Creepers 2 does not mean she will be saved by a patriarchal figure, rather she will combat the monster queer herself, demonstrating her agency and position within this chaotic sphere. In other words, she, like the “monster queer,” is fighting for her own existence in the hostile, chauvinistic world into which she was born. Clover defines this ending as one of two possible types:

“She alone looks death in the face, but she alone also finds the strength either to stay the killer long enough to be rescued (ending A) or to kill him herself (ending B).”[31]

Being rescued versus her ability to kill him herself gives the Final Girl the cogency to reckon with her own “monsters”; and in this case, the monster threatens her future within the male/female, hetero/homosexual binaries laid out by heteronormativity. Furthermore, she becomes the independent figure to which the male victims can turn as they seek asylum, engraining her future role of matriarch. Minxie, therefore, becomes the Creeper’s own monster, as they both struggle to overcome one another. He must continue his pursuit of male victims, his pursuit for existence, while she must struggle against him to guarantee and maintain her status within patriarchal Western society.

At odds with existence, the Final Girl and the monster queer operate within a sphere of predetermined power structures: an evident hierarchy of male/female, hetero/homosexual and normative/non-normative identity formations. This suggests that these binaries are institutionalized constructions, positioning the first identity in the binary in the active role and the secondary position in the passive. To support such a claim, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick argues:

“the shapes of sexuality, and what counts as sexuality, both depend on and affect historical power relationships.”[32]

In other words, the “monster queer’s” sexuality and the Final Girl’s sexuality are at odds with one another, just as the charaters are at odds with one another for existence and acceptance.

Ultimately the Creeper is overcome not at the hands of any one person but because of his limited time to scavenge his isolated setting for potential victims. Moreover, the film’s ending shows the Creeper tied up in a barn, recalling the bleak images of KKK hangings of African Americans in the rural South. And as the Creeper awaits his next spring, so awaits an aged man, ready to combat this “monster queer.” I find the film’s ending suggestive of the queer awaiting for his/her acceptance and the patriarch waiting to deny that acceptance whenever need be.

In conclusion, I have looked at the ways in which the slasher film has been defined, detailing its specific proponents (as informed by Clover’s work), relating the film Jeepers Creepers 2 to its generic conventions and narrative structure. Furthermore, I have attempted to extend Harry Benshoff’s definition of the monster queer in terms of the slasher film. By looking at the slasher in terms of sexuality and not just gendered power structures, I hope to expand Clover’s gender-based assumptions to consider the slasher film’s relationship with (homo)sexuality.

While I have employed a narrative approach with elements of textual analysis, this essay did not permit the space to examine fully the critical reception and/or queer readings of the film that could have further substantiated the analysis. One could also undertake a more detailed exploration of the director’s own sexuality and his widely publicized paedophilic scandal from the late 1980s. Further research on sexuality and the horror film may focus on queer appropriations of the genre both historically and contemporaneously. This will allow for a more thorough examination of the queer undertones in film narratives, especially in horror. It may also open up debates around film spectatorship including the possibility that the gay community has identified with the figure of the monster in a multitude of ways, something that requires much more consideration.

|

|

| This frame, at the onset of the film, provides a spatial and temporal framework for the viewer to negotiate the Creeper’s liminality. | As the bus breaks down on the endless road, the Creeper takes advantage of this desolate space and the victims entrapment within the wide open. |

|

|

| Moreover, if the Creeper can only exist within 23 days ever 23 years his advances towards objects of desire must be hyperbolised, because he will only be visible under these terms. | Sex and food are commonly linked as two naturally human actions. If the Creeper exists in this short period, and cannot perform sexually (assumed through its positioning as the psychotic, slasher figure), then the only alternative for a hyper-repressed figure is to victimise and brutalise. |

To

top![]() Print

version

Print

version![]() JC 54

JC 54![]() Jump

Cut home

Jump

Cut home

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License.