JUMP CUT

A

REVIEW OF CONTEMPORARY MEDIA

![]()

Little Cheung (cont'd)

Cheung hires Ah Fan as an assistant. She and her mother earn a living by washing dishes in an alley for a restaurant.

Ah Fan proves her worth by demanding a customer pay and refusing to take credit.

Fruit Chan's occasional gross-out humor is seen here when from a second story balcony, Cheung drops a tampon into a bully's tea below. The visuals emphasize the joke.

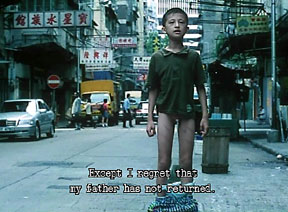

The father punishes his son by making him stand on a piller out on the street, with pants down. The child recites a famous song as a rebellious lament while he pees in the street.

In a lyrical moment the children take a bike ride in Kowloon along the Hong Kong harbor.

They cry out. "Hong Kong is ours." Ah Fan is sure that she and her mainland family will now get papers to stay.

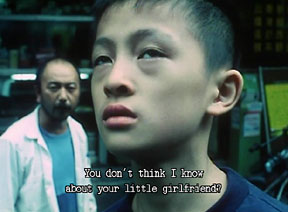

Cheung's father is patriarchal and emotionally cold, so...

...the child turns for comfort to the maid.

But she leaves, and his grandmother, his other family ally, dies.

In school, the children celebrate the handover in a regimented flag-raising ceremony, of which they understand little.

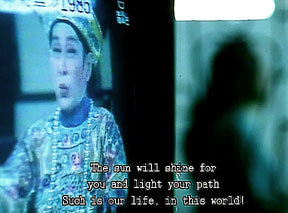

This star's death in 1997 coincided with the takeover. Little Cheung declaimed the lyrics to one of his songs while being punished in the street.

Hollywood Hong Kong

Wong Chi-Keung is a young pimp who has...

...an Internet site where he pimps his lover...

...Ah Lu, who dresses up in many guises for the job...

He is attracted to another prostitute, Tong Tong, also advertising on the Internet. She " looks so Mainland," he says and starts to pursue a relation with her after he runs into her on the streets.

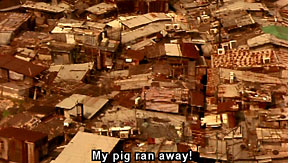

He and the Chu family of butchers and pork vendors live in the Tai Hom shanty town.

Behind and above Tai Hom...

...towers a large apartment complex and shopping center.

I live up there in Hollywood, Tong Tong says to Keung, as they find a moment of intimacy on a grassy slope.

She lives in Plaza Hollywood in an apartment provided by her pimp, "Peter."

It is evident that Fruit Chan is a filmmaker who is deeply concerned with the proletariat's hardships and predicaments. His films transform harsh lived realities, with all their inherent contradictions and ambiguities, into forceful images. He presents the other Hong Kong, not the famous international film center, the glamorously commodified society, or the seductively irresponsible lives of middle class youth, but the inhospitable world of the oppressed and the downtrodden. He avoids the extremes of moral sentimentalism or revolutionary ferocity. His intention is to present the lives of the proletariat as they struggle to survive in a harsh environment.

Fruit Chan's films are melodramatic fantasies in the best sense of the term. He seeks to reimagine proletarian life in Hong Kong, to give it greater imaginative definition, by mobilizing the resources of cinema. Chan's films are important not because they provide us with documentary-like information but rather because they urge us to delve into the inner recesses of marginalized people who encounter large, challenging questions that elude their comprehension. It is their very effort to reimagine the oppressions and functioning of the social order that involve them in efforts at self-definition. Proletarian consciousness, as depicted in Fruit Chan's cinema, is a mixture of social truth, personal knowledge, and wishful thinking—all enframed by cinematic desire.

Fruit Chan's films are works of fantasy, not fantasies of escape but fantasies of confrontation. They confront the harsh realities of the other Hong Kong. They are melodramatic in that they subscribe to a rhetoric of excess. The excess within the narrative structure and the visual style has a direct bearing on the characters' incomprehension as well as their determination to overcome hardships. This excess, which is connected to the performative dynamics of the narrative, points to the fact that the enacted human dramas generate an uncontainable surplus of meaning.

Unlike in the normal film, which obliterates what characters transcend to focus on the main trajectory or resolution of the plot, Chan's films underline the very oppositions the characters seek to transcend. Using a modality of melodramatic fantasy, which Fruit Chan projects into the personal dramas of his characters, his films rely on narratives that need and utilize strategies of excess. Unlike many other filmmakers, Fruit Chan does not displace social issues onto personal acts of criminality in order to occlude social causalities; rather his is an attempt to explore social formations' illusive and protean nature. Chan's use of fantasy and the absurd as modes of exploring social reality is very significant in terms of Marxist aesthetics, because this is exactly the opposite of what formidable Marxist aestheticians like Georg Lukács advocated—the need to stick to realism.

As I stated earlier, the relation between the proletariat and the changing Hong Kong social environment is an important thematic component in Fruit Chan's work. All his characters are shaped by the developments in Hong Kong society, which are of course linked to its economic growth. Hong Kong's evolution from a fishing village to a bustling industrial city and then to a center for service industries and international finance points to the velocity of change in Hong Kong. One consequence of this rapid change has been the inability of low skilled workers to adapt to changing circumstances and seize new opportunities. Part of their tragedy grows out of this inability. Autumn Moon, in Made in Hong Kong, remarks, "The world is moving too fast. Just when you want to adapt to it, it's another brand new world." He seems to be echoing the sentiments of a whole generation of young people in Hong Kong who are caught in the mechanisms of multinational capitalistic intrusions.

Since the 1960s, with Hong Kong rapidly developing under the sign of capitalist modernity, the proletariat as a class has seemed less and less important. The accelerated social development and increased commodification of society, with a premium being on sign value, left the proletariat in an uncomfortable position. Fruit Chan, as a gifted and socially conscious filmmaker is concerned with the issue of how the members of the proletariat can sustain their lives. For example, in The Longest Summer, a group of locals rendered jobless as a result of the disbanding of the British army, choose to rob a bank. Yan, in Durian, Durian and Tong Tong in Hollywood Hong Kong, work as prostitutes to survive. Even the idle gangsters in Made in Hong Kong are busy collecting "protection fees" for their boss. Surviving in an inhospitable society makes all these characters insensitive to human values and human relationships, survival being their primary goal.

In Fruit Chan’s films, we sense that human relationships robbed of sympathy and understanding become reduced to crass self-interest. For example, Yan and Tong Tong appear as good conversationalists only to further the pseudo-relationships of commercial exchange. Little Cheung’s observations also index these deficiencies:

"I already understood a lot when I was nine. My father owns a restaurant. Our Filipina maid is here to make money. My mother plays mahjong in the mahjong parlor for money. Of course, I am no exception. I have known from an early age that money is a dream. It is fantasy. And it is also a future. You can see why everyone in this street is enterprising."

The only sincere relationships are those between Tong Tong and Ah Little, Little Cheung and Ah Fan. Fruit Chan seems to imply that it is a matter of time before these relationships based on trust and innocence will also yield to the calculative and manipulative impulses of adults. In this regard, it is useful to remind ourselves how Karl Marx echoed these sentiments"

"The bourgeois has left remaining no other nexus between man and man than naked self-interest, the callous cash payment."[3]

[open notes in new window]

One of Chan’s strengths as a filmmaker commenting on the social landscape of Hong Kong is his ability to point out the ways in which bourgeois consciousness thus inflects proletarian consciousness.

The year 1997 marked an important watershed in the development of Hong Kong; everyone was concerned with the anxieties generated by this event. Fruit Chan chooses to focus on this impact of this event, as for example in The Longest Summer by combining these anxieties with the predicament of the proletariat as a class. Responding to some critics who saw these character' behavior as meaningless, Fruit Chan observed,

"In 1998 I chanced to meet a group of Hong Kong British army people who were very angry as portrayed in my film. They were so agitated because they had become so unemployable so suddenly in their golden age, and had been abandoned by the British government and the Hong Kong new regime after 1997. How could they find other jobs? Thus, I linked up what I saw and heard and what they felt in making the film."

Fruit Chan sees the new political landscape created by the union of Hong Kong and China in somewhat negative terms. For the proletariat, Chan seems to be saying, the new linkages between Hong Kong and the mother country have not visibly improved their quality of living, but only precipitated greater conflict. The Chinese immigrants who come to Hong Kong to work as prostitutes exemplify this problem, and they also reveal that the transnationalization of labor is a result of globalization. In Hong Kong, Filipina and Indonesian maids, Chinese prostitutes, Indian and Pakistani workers, Nepali women form an essential part of the labor scene. Fruit Chan seeks to capture facets of this phenomenon and its manifold consequences in his films. These migrant workers are looked down upon by the rest of the proletariat class in Hong Kong thereby opening up fissures and tensions within the labor force itself. However, in his films Chan portrays migrant workers, both legal and illegal, with a measure of sympathy, focusing on their unrealized dreams and desires. Thus Yan in Durian Durian hopes to open a boutique and Tong Tong yearns to go to Hollywood. In an interview, Chan discussed his interest in such women's lives:

"I have interviewed and listened to their views, future, and life and work. I have tried to capture something of the struggle of life in the face of unemployment and adverse social and economic changes occurring on the mainland. Nowadays some earn several hundred dollars per month. It is not possible on the mainland. For them, the only way open is to become a prostitute."

|

|

| During this time, authorities remove mainland children from classes and... | ...Fan and her family also get rounded up for deportation. |

Seemingly the family constitutes a contrasting theme to prostitution, but Chan sees the relation between the two. The family constitutes a central institution in Hong Kong films, as indeed in Hong Kong culture in general. In his films, Fruit Chan recognizes the importance of the family and makes use of it as a way of pointing out the sense of alienation that mark human relations as a consequence of the intrusion of crass materialism into the lives of the marginalized. For example, because of the increasing prosperity of the bourgeois, it is common for richer men have mistresses on the mainland, placing undue strains on the family. The plight of children growing up in broken families is also a concern of Chan. His film Made in Hong Kong alludes to the fact that Autumn Moon comes from a broken family and at one point is so angry and agitated that he contemplates killing his father. Fruit Chan uses as a theme the decline of the institution of the family to trace out the stresses brought to bear on human relations caused by the intrusiveness of capitalist modernity.

As he traces the influences of capitalist modernity, Chan also dramatizes the complex ways in which moral corruption has entered into the dispossessed 's and the beleaguered working-class people's struggle for survival, how moral corruption inflects their lives. In The Longest Summer, the family in question is itself engulfed in moral decay. The parents are not proud of Ga Yin but praise their younger son, who has become a gangster, and encourage Ga Yin to follow suit. At one point the father says that no one who tries to live honestly will succeed in life. This skepticism grows out of the economic and social conditions. Fruit Chan, in an interview made the comment,

"A lot of parents only care about whether their children can bring money home and maintain a home for them. They do not care about what they do."

Chan is deeply concerned about how the Chinese family, which was once the central repository of moral values, has now succumbed to powers of moral corruption.

Unlike many Hong Kong film directors, Fruit Chan wishes to examine Hong Kong society from below, opening up new and important angles of vision. In this effort, he has demonstrated, as few other Hong Kong film directors have, the complex ways in which social power is inscribed on human bodies. Chan’s approach highlights the need to understand the workings of classes, how the socially marginalized in the streets connect and disconnect with each other, and how their daily activities relate to the larger world. The grammar of his cinematic imagination is structured to express this felt understanding of the lives of those on the margins. In many of his films, the conflicted life of the proletariat shapes both narrative discourses as well as representational strategies, thereby making such conflict a significant part of his filmic meaning. This is, of course, not to suggest that Chan is a documentary or ethnographic maker of films dealing with the other Hong Kong. His visual style and cinematic imagination represent the exact opposite. Fruit Chan is a creative filmmaker who seeks to illuminate facets of Hong Kong life by converting the lived lives and felt emotions of the disenfranchised into impactful cinematic images that unsettle and destabilize conventional understandings of Hong Kong society. His efforts may not always be successful, or on target, but his ambitions are clear. His films aim to reconfigure proletarian life through innovations in cinematic practices and representational discursivities and intertextualities. His consistent interest in exploring and forging representations of class invest his portraitures with a characteristic vibrancy.

|

|

| ...as a blonde... | ...or as a schoolgirl. |

As a film director, Fruit Chan focuses on the lived experiences, the aspirations, the inbuilt contradictions, of working-class life. His films lead us to recognize the importance of the experiential dimensions of class, the texture of this life, the voice of the un-voiced. A confusion of values, which marks the life of the dispossessed, constitutes the staple of his films. Chan shows us how people respond to events and seek to make sense of their responses in their desperate struggles for survival. Hong Kong, in his films, is a conflictual space of personal survival.

As scholars and activists examine the nature and significance of class in their social inquiry, they often have a pronounced tendency to think in universalist terms. Many refer to Marx as promoting such a viewpoint, although in fairness to Marx, it must be said that scattered in his writings are recognitions that class has also to be understood in culturally specific terms. Fruit Chan’s films serve to emphasize the fact that class consciousness can best be understood in the complex ways in which the dispossessed and the marginalized respond to their distinctive experiences culturally. It is this cultural enframing that gives films like Durian, Durian and Hollywood Hong Kong their distinctive feel. We need to remind ourselves that frames of intelligibility needed to trace out the meanings of Chan’s films are forged on the anvil of culture – in this case, Hong Kong culture. He seems to be implying that capitalist modernity is a battle waged in culturally specific spaces and that it brings together mutually reinforcing and subverting desires derivng from both globalism and localism. He is also directing our attention to the fact that these culturally specific spaces offer us an epistemological vantage point from which to assess the dynamics of class in the modern world. The meanings and self-inventions of working-class lives can be comprehended only in terms of the culturally inflected, experiential nuances of working class experience, in all its ambiguities and contradictions. Social historians like E. P. Thompson, in discussing class, have made the point that it is through experience that structure is transmuted into process, and the subject re-enters into history.[4] What is interesting about Fruit Chan’s films is that he is aiming to dissect Hong Kong society within this kind of materialist and historical problematic.

Related to the way that Fruit Chan ties depictions of class to the specificity of experience is the way in which he combines issues of class and gender, giving greater density and definition to both in the process. This is clearly to be seen in such films as Durian, Durian and Hollywood Hong Kong. Chan's films make clear that men and women do not inhabit the public spaces available to them in identical ways, and that this fact is very pertinent in explorations into class. For example, when he depicts the experience of mainland Chinese prostitutes working in Hong Kong, Fruit Chan is alerting us to the larger fact that technologies of power operate in diverse ways in society in order to maintain class hegemony. In addition, he is showing how gender issues are not confined to relations between makes and females but are vital strands in the hegemonic discourses of modernity and globalism.

Another interesting feature of Fruit Chan’s films is that he does not seek to impose an ethic of individual heroism and triumph on the class structure. His characters, for the most part, do not display a desire to transcend their working-class confines in acts of upward mobility, thereby fortifying the valences and legitimations of the class system. Even when they dream and fantasize, it is through the optics and syntax of working-class life that dreams are accomplished. (By way of contrast, we can see how this impulse for class-transcendence characterizes Hollywood films, as in Pretty Woman.) What Fruit Chan depicts is the inevitability of the class system's structural inequities and the need to think of change not in terms of individual transcendence, but social-structural rearrangement.

To

top![]() Print

version

Print

version![]() JC 49

JC 49 ![]() Jump

Cut home

Jump

Cut home

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License.