JUMP CUT

A

REVIEW OF CONTEMPORARY MEDIA

![]()

The Lion's Den

[La boca del lobo],

dir. Francisco Lombardi

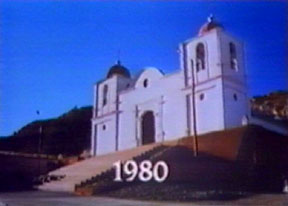

The year 1980 is established in the opening shots, the start of Sendero’s armed struggle. This image of the church overlooking the square is repeated throughout the film, highlighting the site as a point of struggle between Sendero and the army.

A young girl appears in traditional dress with her sheep, staring intently at what is later revealed to be a Sendero placard.

Graffiti shows that Sendero have been or continue to be present in the village.

Vitín and his fellow soldiers contemplate their surroundings...

...noting that the Indians who watch the soldiers set up could be Senderistas.

Indians in the square watch the soldiers change over the post. From Vitín’s perspective, “they” could be Senderistas.

Soldiers take people from their homes and...

...round them up in the square after...

...the Peruvian national flag has been replaced with the Sendero one.

Villagers are forced into the square and the spectator shares their viewpoint of Roca on the steps of the church as he announces the new regulations.

Soldiers stand amidst the villagers and force them to remove their hats and sing the anthem.

Roca stands in front of the imposing image of the church and leads the salute to the Peruvian flag.

The Peruvian national flag dramatically dominates the screen and appears to almost engulf Roca.

Latin American cinema has long taken up the theme of attempting to capture a silenced history (Bedoya 1995; 220). In Peru, this effort has been exacerbated not only by the constraints of state intervention, but also the limited development of a local film industry, which continues to be one of Latin America's most impoverished. Notwithstanding, the country's cinema does provide some of the more explicit accounts of Peru’s years of political violence during the 1980s. What follows is a discussion of two feature films: Francisco Lombardi’s The Lion’s Den (1988; La boca del lobo) and Marianne Eyde’s You Only Live Once (1993; La vida es una sola), in the context of Peruvian historiography and intellectual cultural production.

This essay proposes that the different status accorded to each of these films as representations of Peru's war with Sendero Luminoso (or Shining Path) centers on the competing conceptions of national identity they present and the problematic of screening the Andean subject in Peru.[1][open notes in new window] In The Lion’s Den, Lombardi continues to privilege the dominant discourse of the nation; he critiques the military but also seeks to incorporate the indigenous into a broader national identity. By contrast, in You Only Live Once, Eyde attempts to undermine the legitimising discourse of the nation in favour of a local Andean identity; her film is also critical of the alternative discourse on the nation put forward by the Communist Party.

Peru's political context

In order to contextualize this discussion, first I want to turn to the difficulty of historicizing the period of political violence in Peru, which lasted through the 1980s and early 1990s. During this time, the country approached civil war with the rise of armed struggle led by the Communist Party of Peru-Sendero Luminoso (PCP-SL), a conflict which saw more than 30,000 mostly indigenous peasants killed.[2]

Sendero emerged at a time when the left in Peru appeared defeated. The guerrilla movement led by Hugo Blanco had largely disappeared by the 1960s, and a number of left intellectuals had been recruited into the service of the state during the military left dictatorship of Velasco. Having undergone a series of schisms, this branch of the Communist Party emerged in 1970 from a provincial university setting in Ayacucho, a major Andean center largely neglected by the state, whose financial and political center was (and continues to be) based in the capital, Lima. Sendero was based on Maoist ideology and a reclaiming of Peruvian Marxist José Carlos Mariátegui. By appropriating the work of Mariátegui, Sendero could emphasise its localized application of Maoism and create its own “indigenous” Marxism. It launched its People’s War in 1980 just when organised international communism was in retreat.

One of the conspicuous aspects about scholarship on Sendero is that the movement was not taken seriously when it first emerged on Peru’s political scene; initially, it went largely unnoticed by historians and the media alike. Part of this neglect may be attributed to the conceptual currency of “Andeanism,” a term used by Orin Starn, useful for understanding contemporary colonial intellectual approaches to the indigenous subject in the Andean region. Drawing on Edward Saïd’s critique of “Orientalism,” Starn shows how Andeanist scholars construct their knowledge of the Andean region based on their own preconceived notion of what it means to be “Andean.” This kind of scholarship is embedded in colonial attitudes and conforms to the idea of the indigenous as unchanging, timeless, and therefore outside of history. In terms of the emergence of Sendero, what Starn argues is that while Andeanist anthropologists of the 1960s and 1970s were busy identifying traditional markers of indigenous identity – such as cultural rituals, community organization, spiritual beliefs, language structures – they were in fact totally out of touch with the local reality, which was that a communist party was successfully mobilizing amongst a disaffected peasantry in preparation for armed insurrection.

Early studies of Sendero were for the most part dismissive of the organization as an outside, Western-stylized Marxist movement, said it violently imposed its vision of society on a passive, helpless indigenous people, and concluded that it would rapidly disappear. As Steve Stern has observed, when historians did approach the subject of Sendero, it was framed as,

“Enigma, exoticism, surprise … a freakish evil force outside the main contours of Peruvian social and political history – more an invention of evil masterminds and an expression, perhaps, of the peculiarity of a particular regional milieu than a logical culmination or byproduct of Peruvian history” (Stern 1-2).

In order to assert their own moral distance from the movement, others contributed to the language of enigma and freakishness, or elected not to deal with the subject at all.

More recent scholarship on Sendero has shifted to reassess the movement critically in order to address how this period of Peru’s history for the country’s Andean population became dehistoricized. Historians now see that Sendero's rise responded to concrete historical developments in Peru. This period saw political upheaval, government corruption, a weak left, and racism towards the indigenous population — who continued to live in poverty and be excluded from political decision-making (see the volume by Stern). Such exclusion allowed Sendero to operate amongst the rural indigenous peasantry. The organization was largely unnoticed in its early years in a region that had been historically neglected by successive governments. Political, social and intellectual attitudes towards the indigenous as outside history and unchanging were condensed onto attitudes towards Sendero.

An important text for Sendero was Ayacucho: Hunger and Hope by Peruvian anthropologist Antonio Díaz Martínez. Largely ignored by Andeanist anthropologists, it highlighted the poverty and intense class-differences in the region. Díaz Martínez’s study presented the Andean peasant as dynamic and changing. While Sendero did not sustain this attitude towards the Andean in its practical work, the organization largely had success in recruiting from impoverished indigenous Andean communities because it understood indigenous identity.

In the nineteenth century, early attempts to exoticize the Indian saw the development of literary indigenismo, a movement that fictionalized the ways in which the trilogy of landowner, priest and local governor worked together to exploit and oppress indigenous communities.[3] Indigenismo was a product of urban, educated, white intellectuals. It was tied up with liberal ideologies that sought to bring the indigenous population into the nation-state through programmes such as education. Its ideological development saw indigenismo being openly extolled by the State in the early 1920s in order to co-opt the indigenous population by regulating indigenous communities. The preoccupation with the indigenous figure reflected the deep cultural divide in Peru that existed between primarily the sierra and the coastal regions since the colonial era. This divide is also a theme of the two films discussed below.

Army as outsider

The Lion’s Den and You Only Live Once reveal the effects of regional differences on understanding, and creating, political violence in Andean Peru. That Sendero's early activities were ignored in the media is referred to directly in the opening titles of The Lion’s Den, which state that the film is “based on true facts which occurred between 1980 and 1983.” Along the same thread as Lombardi’s earlier film, an adaptation of the novel La ciudad y los perros, The Lion’s Den denounces the harsh tactics of the Peruvian military and the psychological conflicts these generate amongst its officers. The narrative's period coincides with the Peruvian military’s early strategy in combating Sendero. They waged a genocidal campaign and the film has a reference to the “dirty war,” a term resonant of Argentina’s Dirty War, characterized by the military's ruthless, systematic program to clamp down on political opposition. This reference in the film introduces us to later scenes of indiscriminate violence carried out by the military against the rural indigenous community in order to stamp out Sendero.

The Lion’s Den begins by showing replacements sent to a military post in a small rural town near Ayacucho, Chuspi. The narrative centres on the figure of Vitín, a young soldier, and his experience of life in the army and the sierra when he transfers to this unpopular emergency zone in order to secure a rapid career path. The military have been sent there to contain Sendero. Consistent with military policy at the time, the men sent to fight the peasants are from the coast and therefore do not identify with the local population. The establishing scenes depicting the arrival of the military highlight the isolation of the town they have been sent to. Shots of the mountains and the trucks carrying the soldiers and supplies coming up the trailing road accentuate the remoteness of the village, just as the war with Sendero was distant from Peru’s urban populations. These scenes of the landscape emphasize both the disruption that occurs with the soldiers’ arrival, and the foreignness of the village. From the soldiers’ perspective, they are entering a foreign land.

This sense of disruption is further enhanced with the early image of an indigenous girl with her small herd of sheep, staring at Sendero placards and graffiti in the square. While she seems indifferent, it is clear that something is not right. The theme of descent into chaos, caused by the activities of Sendero, gets played out in the film as the events unfold. It first seems that there is hope in that the girl, as with her village, can be rescued by the military. The closing scenes reverse this. There the girl looks on as Vitín leaves the village with Andean music playing in the background; she has not been protected by the military and her world remains in a state of chaos.

Lombardi relies on exoticized notions of the Andean with these images. He presents a young indigenous girl in full traditional dress, innocent, waiting to be rescued by the outsider, and uses this kind of imagery to foreground a key event in the film whereby a group of villagers are herded like animals and slaughtered by the military. He also reinforces relations between the people and the land through the the way he depicts animals and cultivation of food.

While these associations between geography and people are not erroneous in the sense of traditional indigenous relations with the land, they serve a dual purpose in The Lion’s Den. In the film, they reinforce Andeanist ideas about the region's indigenous people (the local people are a part of the land) and also to highlight the cultural clash between soldiers and villagers (they, as part of Sendero, must be conquered). The military's inability to relate to the people is a result of their cultural differences, which are also a means used by them to justify their brutal tactics.[4] The soldiers cannot discern who belongs to Sendero and the movement is never explicitly presented in the film or to the soldiers. Any one of the peasants in the village could be a member of the organization.

In surveying his surroundings marked by walls covered in PCP-SL graffiti, Vitín can tell that “they” have already been there. Using only the personal pronoun, he looks at the villagers in the square and observes that “they” could still be there. By not naming Sendero, Lombardi emphasizes how ominous and alien the sierra is to the young military men who could just as well be in another country. They miss their own cultural referents such as food and music. They do not cope well with the change in climate and terrain that is home to Peru’s predominantly indigenous population. We also experience Vitín’s initial anxiety, paving the way for his disillusionment with the military.

Even though the soldiers are Peruvian, their racism prevents them from understanding what Sendero is; it also keeps them from seeking the townspeople's co-operation in the fight with Sendero. The army’s first activity takes place when the Peruvian national flag erected above the barracks has been tauntingly replaced overnight by the PCP-SL hammer and sickle flag. A series of reprisals follow. In order to find the culprit, the soldiers search every home and finally find evidence in the shop of a retablista.[5] He is tortured after not cooperating in answering their questions until they discover that he only speaks Quechua. Tellingly, the soldiers interpret this linguistic barrier not as revealing the incongruity of the military’s presence in the sierra, but instead as giving evidence to the backwardness of the people who reside there. There follows a program of national retraining in a public ceremony of pledging allegiance to the Peruvian flag. Roca appears at the top of the stairs, enhancing his authority over the peasants below who look indifferent when he announces:

“Now we will pay tribute to our only flag, to the flag of our homeland.”

Everyone is then coerced into singing the national anthem, nudged by soldier’s guns if unenthusiastic. Only valid is the flag of the colonial nation, not the red flag of Sendero. Yet the symbol of the Peruvian flag is also meaningless to the indigenous peasants gathered in the square, for they are not full members of the nation. Significantly, Vitín erects the Peruvian national flag in the first scenes following the attack on their station. In a sense, he becomes the true defender of the national from his initial support for military operations in Chuspi, loyally following his superiors’ commands, to his later defection following his increased criticism of what defending the national really entails.

The film highlights the army’s inability to relate to the villagers in order to reveal the harsh reality of collective punishment and ignorance about indigenous culture. Following reports that Sendero were present in the village the night before, the soldiers visit a local farmer and discover that the guerrillas took a cow from him. In order to assert their own authority and status over Sendero, the soldiers kill a cow for the military. The unnecessary slaughter of animals is anathema to the villagers, whose relation to the natural world conflicts with that of the Westernized soldiers. The people's livestock and lands form part of their livelihoods and they cannot afford to feed both armies.

The narrative theme of a national army at odds with its Andean environment is reinforced with the rape of an indigenous woman, Julia. Sendero, buried in the indigenous population, is like the land and must be conquered. However, this level of colonization acquires another dimension with Julia’s rape, which reinforces the association of the colonized and land with the feminine.[6] While the military presumably are in the village to protect the community, the rape goes unpunished as Vitín protects his fellow soldier and rapist, Quique.

It is during a community fiesta that things come to a head. Quique tries to force his way in and is accused by party goers of raping Julia. He uses his authority as a soldier to break up the fiesta, and then a false accusation leads to suspected senderistas being rounded up, some of whom are tortured. The incident culminates in the massacre of thirty peasants, whose bodies are blown up in order to destroy the evidence. It is at this point that Vitín rebels against his commander and deserts from the army. The association of the feminine with conquest is reinforced when Roca accuses Vitín of not being “man enough” to shoot the villagers; for Vitín this crucial turning point reveals to him that the question of “them” or “us” can never work. The army will always be against the people.

To

top![]() Print

version

Print

version![]() JC 49

JC 49 ![]() Jump

Cut home

Jump

Cut home

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License.