JUMP CUT

A

REVIEW OF CONTEMPORARY MEDIA

![]()

Star Trek space battle and ...

... the construction of the Enterprise as well as its interiors are CGI creations.

The 2009 version of the Enterprise bridge set: This set is much brighter, whiter, and shinier than the original series’ set. Abrams designed the ring of lights around the set to help generate flares during shooting.

Mr. Spock (Zachary Quinto) confronts Jim Kirk: This shot and the next three are taken from the critical scene where Kirk goads Spock over his lack of emotion about his mother’s death. Spock tries to kill Kirk, prompting his realization that he is too emotionally compromised to retain command of the ship. His resignation makes Kirk acting captain of the ship. These shots are heavily compromised with analog flares.

Kirk goads Spock into a fight to prove Spock’s lack of fitness to command the Enterprise.

Kirk goads Spock into a fight to prove Spock’s lack of fitness to command the Enterprise.

Spock nearly chokes Kirk to death, only to stop when his father quietly calls his name.

Following the fight and Spock’s resignation of command, Jim Kirk assumes the captaincy of the ship and takes his station on the bridge.

To hide from the enemy ship, the Enterprise secretes itself in the mists of Saturn’s moon, Titan. Note flares.

The Enterprise against the rings of Saturn. This is one of the shots of the ship that is pristine, lacking flares or other visual artifacts. It looks very much like a screensaver. (Note: if you turn the image sideways, the Enterprise cuts the space between Saturn and the rings into a replica of the Starfleet emblem.)

Crew uniforms. Kirk does not wear the gold command shirt until the final scene of the film.

Deaths in battle. The Enterprise crew discovers that the Narada has destroyed the rest of the fleet.

Despite the major roles played by Spock and Chekhov in the defeat of the enemy ship, only Kirk is awarded a medal.

Images from Public Enemies

Dillinger and his crew rob a bank in Chicago.

Billie Frechette (Marion Cotillard) goes on a date with Dillinger wearing a three-dollar dress.

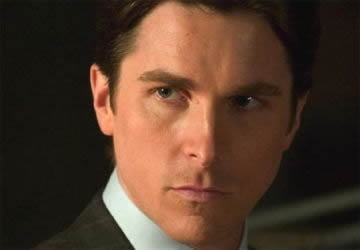

FBI Agent Melvin Purvis (Christian Bale) and Director J.E. Hoover (Billy Crudup) at a press conference declaring Dillinger Public Enemy #1. Hoover uses the publicity to get Congress to increase FBI funding allocation to fight the national scourge of crime.

Dillinger being transferred back to Indiana to stand trial.

Frechette with glamor lighting even in a crowd.

Depp filmed with "stylized clarity" throughout.

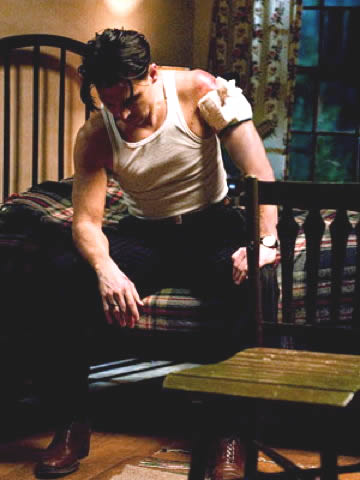

Depp’s Dillinger as a wounded, solitary hero.

![]()

Light bouncing:

digital processes illuminate the cultural past

As digital tools undergo industry diffusion and standardization, professional filmmakers are defining a relationship between analog and digital that situates “film” as an emotional register and “digital” as a sterile image capture process. This opposition rests on the realist ontology of film with its claim that the indexical relationship of object and film image is absent in digital recording. In this model, the lack of shared light bouncing between the object and the film plane, and the loss of image information through sampling differentiate digital recording from the perceived holistic nature of analog recording. One striking effect of this labeling is a resurgence of a type of textual nostalgia for film, and for effects associated with film. Such nostalgia complicates the emergence of any aesthetic approach that attempts to identify potentially unique visual and aural elements of digital cinema technologies.

Directors and cinematographers frequently use emotionally laden terms to describe digital and analog processes. The breakdown runs roughly along lines of “emotional, warm, live, and organic” for analog footage, including analog effects (post production). “Sterile, cold, perfect, and artificial” feature in descriptions of digital effects. This breakdown has tended to hold discursive prominence since approximately 2005, when I began tracking industry articles on this issue.

The director of the 2009 Star Trek film, J.J. Abrams, is one filmmaker thinking of cinema in these terms. His aesthetic strategies aim to reduce or suppress the presence of digital effects onscreen. This approach to digital technology reveals a certain nostalgia for film, one that echoes Star Trek’s resurrection of its own cultural history. This dual nostalgia operates to construct a futuristic world that revisions U.S. cultural past, while ignoring narrative references to contemporary political events.

However, a number of directors are now turning almost exclusively to digital acquisition and in their interviews, a somewhat different discourse has emerged. Michael Mann, director of Public Enemies (2009), used almost entirely digital acquisition and his description of his reasons for choosing it cite a need to avoid nostalgia, and to create images that are “detailed, specific, and textured as the reality they (audience) see right now.”[1] [open notes in new window] The filmmakers largely achieved this surface through digital manipulation done in the camera.

This comment speaks to a superior reality claim that many digital advocates make, one which contradicts the claim made by film advocated. Mann’s comment also adds notions of historical specificity, objectivity and anti-nostalgia to the mix, constructing a discourse that turns on a major conundrum: the achievement of an objective surface clarity through in-camera digital image manipulation.

I will analyze these two films for several reasons. Star Trek deals with the cultural past (the franchise) set in a fictional alternative future created by combining CGI and analog elements, including both digital and analog lens flares.[2] Public Enemies attempts to construct a historically specific visualization of a cultural past, the gangster mythos, that synthesizes historic events, places, and people with cultural histories of movies and film. These films represent two variations of looking at different registers of the past: a fictional future drawing on a cultural past and a past created in the image of the present through contemporary technologies. I am going to consider these films’ relationships to cinematic pasts through the concept of technostalgia — use of new technologies to mimic older one.

Because digital and photochemical processes coexist in production, a type of dialectic occurs in a number of sites: production processes, labor organization, and visible organization of the film itself. I first wish to consider how the cinematic technostalgia, which digital processes are complicit in producing, emerges.

Films using digital processes to recapture approaches to cinema from a “classic” era or to reproduce a look from another medium, construct a form of cinematic nostalgia. In some cases, nostalgia emerges through the addition of digitized photochemical elements like grain, blur, halation, and scratches. However, nostalgic elements coexist with elements of innovation, thus embodying the dialectic between photochemical and digital processes that Lev Manovich discusses.[3] A number of films released in the last six years have used digital technology to reproduce nostalgic elements. Although the filmmakers offer various surface reasons for these films’ production of nostalgic effects, all are more thoroughly theorized through the notion of the digital dialectic.[4] The use of digital processes to simulate analog effects indicates an unease with the current liminal status of defining film production[5] and works nostalgically to recall “film” to the screen in the midst of CGI spectacle.

Star Trek

Star Trek combines analog image acquisition with extensive CGI images and special effects. Unlike earlier Star Trek films, the latest version uses no models whatsoever of the ship, creating the iconic starship Enterprise entirely through CGI. The iconic starship Enterprise is an entirely CGI creation.[6]

Some of the techniques used in the film are generated both by analog methods and CGI. Live action camera shake is used in a number of scenes, and was generated by the director tapping the camera. However, virtual camera shake also appears in the film. Industrial Light and Magic developed some animation tools to reproduce that in the CGI scenes. The special effects supervisor

“…applied camera shake via small rotational motion capture sensor on a tripod at their workstation…hooked sensor up to the CG camera on our animation inside Zeno….tapped the desk in the same way that J.J. Abrams (director) did on set and tripod sensor picked up vibration and laid it onto the smooth CG camera moves.” [7]

It’s possible that the method of generating the live action shakes has influenced the combination of software with simple human action used to generate shake on CG camera movement. This insertion of human capacity into the CG process represents an attempt at intervening into digital systems which the director characterizes as perfect:

“One of the things that I have always been very conscious of was having visual effects shots feel as if they were being filmed by a live camera operator, not by a perfect prescient computer…” [8]

The most prominent visual artifacts in the film are the lens flares. Lens flare occurs created when incidental (sometimes defined as “non-image forming”) light hits the lens at an angle that causes it to bounce between lens elements. The resulting flare appears on the photographed image as a hazy polygon of bright light, a smear, or both. Lens flares can also be digitally simulated, and then added to other CGI or analog images. Under the conventions of classical Hollywood cinematography, lens flares were considered a mistake; however during the second half of the 20th century, the status of lens flare shifted, and this artifact became a acceptable visual device.[9]

In this film, flares occur in scenes in Iowa, on the bridge of the Enterprise, in Spock’s school on Vulcan, during the shuttle ride from Earth to the Enterprise, and in many other sequences. In contrast, some shots, like the Enterprise shuttle carrying Pike to the Narada (enemy ship), and the shot of the Enterprise rising out of the mists of Titan, are pristine, and have no flares. Neither textual analysis by itself, or a combination of the text and director interviews provides a consistent strategy for deploying these visual artifacts. The flares appear in all sorts of scenes in all temporal registers. In other words, they can be tied to specifically coded concepts only with great theoretical contortions. Abrams says he wished to give a sense of something “spectacular” happening off screen. Flares seem to signal, for Abrams at least, only spatial and reality effects, not textual symbolic meanings.

Flares are generated three ways in this film: through the use of lighting practicals, through ordinary flashlights held by crew members positioned just outside camera range, and through computer generation. ILM developed proprietary software called Sunspot to generate flares. These computer-generated flares can be seen in footage of the ships in space, for example.

Abrams argues that these flares are organic and a resist the sterility of the computer generated image. Since he generates a number of them digitally, his argument loses some of its persuasive power. His choice to shoot on film was intended to “balance” the thousands of effects shots.[10] The “efficiency” argument also appears in Abrams’ comments about his choices between digital or analog processes for specific effects. In the same article online, he also states that he thought shooting digital would take longer to achieve the effect he wanted in the live action footage (ibid). This is arguable, but improbable.

Although Abrams talks quite frequently about digital images’ sterility, the concept is difficult to pin down. What does he mean by sterile, I would ask. There are a number of visual cues embedded in each shot in the film that can produce emotional effects such as dialogue, color, motion, sound, and acting. So the question arises: Are the actors being treated as just another effect? Lens flares obscure their faces in several key scenes, including a key confrontation between Kirk (Chris Pine) and Spock (Zachary Quinto). In this scene, Kirk goads Spock into a fight, forcing him to admit to emotional compromise, and to step down as acting captain. This allows Kirk to take over the ship, which is a turning point in the plot. Establishing Kirk as the young captain of the Enterprise is also the major point of the franchise reboot initiated by this film. Such a scene would seem to require visual elements that concentrate our focus on the character conflict. Instead, the flares obscure the actors’ faces. Acting, a human-centered element, is a major way to keep any scene from seeming sterile, yet the director privileges analog flares over acting. Perhaps Abrams refers to visually sterile images? Again, color, motion, depth, and sound all provide a range of cues for the audience. I think the argument about sterility might be what he perceives in digital shots, but it is not an argument that I find persuasive.

Although the flares seem omnipresent in the film, there are some pristine images. The shot of the Enterprise after it has risen out of the mists of Titan has no flares, and neither do shots of Captain Pike (Bruce Greenwood) taking a shuttlecraft to the enemy ship. The Titan shot looks like it was planned as the potential “screensaver” shot, which might explain its lack of flares. However, there remains no consistent patterning to the presence or absence of flares in the film. Enterprise/Titan image. The pristine quality of the shot also speaks to the technological fetishism that surrounds the Enterprise. It’s debatable whether or not audiences even perceive switches from digital to analog images switches other the obvious “space” shots which some audience members assume are digital shots. Some Trek fans posting on bulletin boards thought that the Enterprise was a model, as it had been in earlier films. The current combinative status of filmmaking will produce such questions for a while.

Star Trek’s art design provides some callback to the original television series. The main group of characters, the uniforms, and many catchphrases, like McCoy’s “pointy-eared” comments about Spock, and Spock’s “Live Long and Prosper,” originated in that series. However, the exterior and interior designs of the Enterprise differ somewhat from the original ones. Not everything in the film is nostalgic, however. This version has minor cosmetic differences on the outside but major changes in the interior sets. The bridge has lost its somewhat functional, bare look and now is very bright and well lighted. The wall surfaces are ultra-white and composed of reflective materials. Some of this lighting and reflective quality accommodates Abrams’ desires for flares. However, the bridge also looks a bit like an iPod or other Apple products, which also emphasize pleasing reflective surface qualities in the casings. This version of future technology embodies the future vision of the early twenty-first century, rather than recalling the mid- twentieth century.

The uniforms, however, remain squarely in the 1960s, with women put back into mini-skirt and styled to echo 1960s hairstyles and facial makeup, particularly the “mod” blue and green eye shadows worn by some characters.[11]. We see occasional women in pants, but most wear the miniskirt, as does the only major female character, Lt. Uhura (Zoe Saldana). The costuming also sexualizes the women crew of the Enterprise, and the insistence on “honoring canon” with the mini skirt ignores the shifting terrain of feminism in the past forty years. The men wear the same red, blue, and gold shirts of the original series

The crew itself embodies a type of nostalgia as well. Original Star Trek shows had a somewhat deserved reputation for diversity, since they featured a prominent black woman and Asian American male character. However, rather than construct a contemporary vision of diversity equivalent to that of the 1960s series, this film slavishly recreates that same breakdown of characters, which no longer looks so diverse. Starfleet is still basically a white male universe, with all men of color, and all women in supporting roles. The film does not even acknowledge the intervening years of the feminist movement, and takes for granted that we are all still happy to see the utopian Star Trek world running happily along 1960s lines.[12]

The film also ignores possible connections to contemporary issues. Starfleet musters the young cadets into the fleet on an emergency basis. They are answering a “distress call” that turns out to be an enemy attack: a serious case of bad intelligence. When the Enterprise arrives on the scene, all the other ships carrying the untried cadets have been destroyed. The Enterprise has several hundred crewmembers; given the amount of wreckage onscreen, casualties must have been in the thousands. However, they are never mentioned in the film, nor is their sacrifice recognized. They are simply buried by the narrative.

This obviously parallels with the United States sending troops to Iraq on the “weapons of mass destruction” intelligence, and then President Bush’s mandate refusing to allow any of the returned soldiers’ coffins to be photographed at Dover Air Force Base. Star Trek ends with a medal ceremony, which valorizes the individual white male hero, Kirk, and ignores the dead, and the other Enterprise crew who contributed significantly to the destruction of the enemy.

Star Trek’s resolute omission of potential connections to contemporary political and cultural life is expressed across the text. Nostalgia operates narratively through callbacks to a forty-year old version of diversity, a recentering of white male authority, and operates visually through the art design, and the nostalgic use of digital technologies to recreate analog artifacts.

Public Enemies

This film is all digital acquisition, except for the slow-motion sequence of Dillinger’s death. Director Michael Mann claims that digital acquisition allows on-set manipulation of some elements, such as increased black saturation and amped up white highlights, to yield “hyperreal image of the past” that “moves away from film and its established aesthetics.”[13]

Mann and his DP, Dante Spinotti, tested film cameras side by side with the Sony F23 HD camera. They found that the film setup yielded better tonal range but the digital system performed better at reading into shadows and had better resolution (ibid.) While many love film for its perceived “warmth,” tests like this provide evidence that warm/cold and sterile/emotional are artificial dichotomies. Clearly each acquisition method provides specific aesthetic choices, and post-production manipulation offers even more possibilities for each acquisition medium.

Given this technical knowledge, the filmmakers believed that it should be possible to produce a set of images that create a sense of immediacy rather than a period film, to render the past in a contemporary look. Mann states that the digital acquisition allowed a

“stylized clarity, and the audience to ‘see textures in detail.'”[14]

The lively crisp surface prompts him to consider his film Public Enemies as a critical, contemporary vision of the past.

This implies that HD cinema processes offer the chance to construct anti-nostalgic images by opening up a space in which the usual aestheticizing of the past does not hold the sway it does in film conventions. This notion ignores the in-camera digital manipulation of the image that produces this surface clarity. It also reproduces an error often associated with popular discourse on forms of realism: that it is somehow an absence of stylization.

The film contains, however, a mixture of romanticism and critical distance. It creates a romanticized picture of John Dillinger (Johnny Depp) and Billie Frechette’s (Marion Cotillard) relationship through the use of lengthy closeups and medium shots of the two as their relationship develops. Certainly Frechette receives glamour lighting in many shots onscreen, as does Dillinger. Her figure, while solidifying the romanticized image of the gentlemanly outlaw, also provides a possibility of social critique. Frechette is half Potawatomie and quite poor. When he takes her to an upscale restaurant, she notices everyone staring. He tells her it’s because of her beauty and she responds that it’s really because they’ve never had a girl in here wearing a three dollar dress before. Frechette’s character creates occasional moments of class or race awareness, but these are not well developed into a critique.

Dillinger, as the paradigmatic old-fashioned outlaw, displays many romanticized elements of that mythos. When robbing a bank, he returns a customer’s few dollars, stating he is there to rob the bank, not the people, a moment seen in many other gangster films, including Bonnie and Clyde. Dillinger also gives his elegant topcoat to a young woman he takes hostage from the bank, and generally addresses all women with respect. These qualities soften his image and create more sympathy for him. They also recirculate the notion that individual crime is more populist and somehow honorable than corporate crime.

“Stylized clarity” does operate in many sections of the film. The surface textures are crisply delineated, and the immediacy of HD recording gives the image a livelier look. Granted, these are largely perceptual qualities, but the liveness of video is something that has been noted for years, even for standard definition video. This allows the narrative overall to function as a displaced version of post 9-11 USA. The film depicts the corporatization of crime in the move away from outlaw gangsters like Dillinger toward organized large-scale book and fraud operations. The script also details the contemporaneous phenomenon of the Federal Bureau of Investigation using the hunt for “public enemies” like Dillinger and Pretty Boy Floyd to justify its requests for more manpower and resources, and therefore to become a much more powerful, and pervasive law enforcement agency. These developments have a current resonance as they echo the preeminence of corporate crime in the past decade and the growth of national security agencies following September 11, 2001.

The technological choices in Public Enemies serve this thematic development well by providing visual cues that move audiences away from established ways of looking at the past. The problem with this idea is that, at its worst and most simplistic, it’s simply technological determinism. However, one crucial difference between the analog and digital cinema production lies in its immediate feedback, and in the ability to set up on-set monitoring systems that give representations of color and framing, congruent with the image that ends up on the film copies struck for distribution. This ability allows filmmakers to shoot and make adjustments as they are capturing the images, not wait until postproduction. It relocates a certain number of aesthetic decisions into the production phase.

The significance of making more aesthetic decisions at the time of shooting extends beyond the possible realignment of the cinematic workflow. It allows filmmakers to see the historical fiction being filmed through the lens of the in-camera effects and to respond to the meanings of the text-in-development without reference to established conventions of analog filmmaking.

Frederic Jameson’s idea of history as "a vast collection of images" that can be revisited many times for the spectator’s pleasure[15] is a productive way to think through this issue. In the case of Public Enemies, the filmmakers attempt to counter this tendency to nostalgic pleasure through visual strategies that differ from previous film conventions, and a plot structure that invites the audience to consider the relationships of crime, politics, and national security. In Star Trek, the filmmakers tweaked a canonical media past, combining new design elements, with elements from the original series and the first motion picture. Unlike Public Enemies, Star Trek’s narrative elaborately ignores any possible political connection between plot events and contemporary global conflict. The film suppresses these political connections in favor of a hermetically sealed narrative that relates primarily to the visual codes of the recent media past. Mann however, seeks a connection between his HD aesthetic and the political issues referenced by the text.

As HD cinema develops, and standardizes camera technology, a new set of aesthetic conventions will emerge and become institutionalized within mainstream cinema. Right now, these conventions are very fluid, and experiments like Mann’s provide rich material to consider the implications of this technological shift.

To

top![]() Print

version

Print

version![]() JC 52

JC 52 ![]() Jump

Cut home

Jump

Cut home

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License.