JUMP CUT

A

REVIEW OF CONTEMPORARY MEDIA

![]()

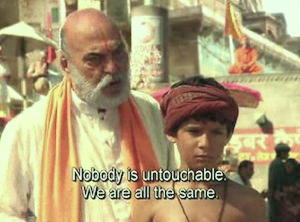

Shankar and Opash confrontation:

The boy Bahuan, an untouchable.

"We are all the same."

"You don't know what you are saying."

"I am a trader. I have a caste."

"The god that lives in you is the same that lives in him."

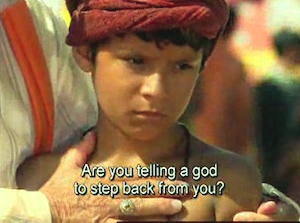

Telling god to step back?

Maya and Surya fight in the kitchen:

In Caminho das Indias the ongoing rivalry between ...

... the main female protagonist Maya and ...

Dance between Maya and Raj:

Maya dances for her husband Raj.

Maya’s gestures and the setting evokes Bollywood’s courtesan genre.

Raj looks on while Maya dances for him

In the courtesan genre flickering flame symbolizes passion.

Maya glances at Raj seductively.

Raj smiles in approval.

Raj joins Maya in the performance and the dance ends in a passionate kiss. The song therefore becomes emblematic of Maya’s romantic journey.

Locating Bollywood in the story

In terms of subject matter the telenovela evokes the classic Bollywood story line. It begins as a story of impossible and forbidden love; caste difference separates the lovelorn protagonists. From Himanshu Rai’s Achhut Kanya/Untouchable Girl (1936) to Shyam Benegal’s Ankur/The Seedling (1974), Satyajit Ray’s Sadgati/The Deliverance (1981), Shekhar Kapoor’s Bandit Queen (1993), K. Bikram Singh’s Tarpan/The Absolution (1994) to the more recent films Aarakshan/Reservation (2011) and Khap (2011), there have been many alternative Bollywood narratives that overtly address the issue of caste based discrimination in India. Even within the more mainstream “masala” Bollywood fare such as Omkara (2006, a remake of Shakespeare’s Othello where the black moor was substituted by a low caste political gangster) and Eklavya –The Royal Guard (2007) caste difference is often the main source of conflict (Dhaliwal 2010).

Achhuut Kanya/ Untouchable Girl (1936) was one of the first representations of the caste issue through film. It was the love story of an untouchable girl and a Brahmin boy. Then came Bimal Roy’s Sujata (1959)that portrayed the suffering and predicaments of an untouchable girl growing up in a Brahmin family. These early films placed caste difference at the center of the romantic conflict in the story. However, the lower caste protagonists in both these films are women, Omkara Bollywood’s more recent romances on the other hand is the story of a lower caste male protagonist. He is the illegitimate son of a lower caste woman and a high caste politician; hence his real caste status is “debatable.” The community though thinks of him as a low caste “bastard” but refrains from discriminating against him since Omi possesses a lot of political influence. He falls in love and elopes with his sweetheart Dolly, the local lawyer’s daughter who happens to be a Brahmin.[12] [open endnotes in new window] This transgression causes resentment and furor in the community. Like Omkara, Bahuan’s caste status in the telenovela remains ambiguous (he is the adopted Dalit son of a rich Brahmin man ) until he falls in love with Maya and wants to marry her. The telenovela also features a scene where Bahuan tries to elope with Maya on her wedding day. This scene is strikingly similar to Omkara where Omi elopes with Dolly on the day of Dolly’s wedding. Additionally, the popular song Beedi Jalaile from the film Omkara features in the opening credits of all episodes of the telenovela. Evidently, class conflict as represented in Omkara appears to be an inspiration for Caminho das Indias.

Breaking caste and class barriers has been a running theme in Bollywood films. There are numerous other films that highlight caste and related class difference as the main cause that prevents the lovers from getting married. Some Bollywood films merely use caste difference as a plotline while several others offer a sensitive portrayal of caste and usually have a reformative focus; Caminho das Indias and its representation of caste falls somewhere between these two. The opening scene of Caminho das Indias begins on the banks of the river Ganga in Varanasi where Shanker a devout and learned Brahmin prays to the river deity and chants “jai Ganga Mata ki” (hail mother Ganga/Ganges).[13]The atmosphere is one of religious devotion and piety that gets disrupted when Opash’s (another devout offering prayers on the steps of the ghat[14]) son touches a dalit[15] boy. The son is reprimanded by Opash for touching an untouchable. Shankar, who had been observing the scene, comes to dalit boy’s rescue.

“Shankar: Bhagwan ke Liye (For God’s sake), nobody is untouchable, we are all the same

Opash: Arrey Baba (Oh, my goodness), you don’t know what you are saying. An untouchable the same as me? I am a Vaishya? I am a trader, I’ve got caste. Step back boy.

Shankar: The God that lives in you is the same that lives in him. Are you telling a God to step back from you?”

This exchange between Shankar and Opash sets the tone for the telenovela.

- It identifies caste as an important social issue that will be relevant to the story and plot.

- It shows the perspective of the telenovela as reformative.

- It advances the plot by identifying the lead protagonists Raj and Bahuan and establishes caste as a divisive line between them.

- And lastly, because of the exchange Shankar learns that the Dalit boy’s parents die due to caste atrocities and adopts him as his own son.

Much like Bimal Roy’s Sujata, the dalit boy Bahuan is brought up by a Brahmin family and like Sujata, Bahuan too feels and understands that he is different. Upon his return from the United States after getting a Ph.D. in informatics Bahuan tells Shankar about a job offer he has received and expresses his intent to live in United States. Shankar responds by saying that “going to college in the U.S. does not make you American.” Bahuan then points to the stigma and detrimental social status he possesses in his homeland because of his caste. Although he is not American, in the US he will “not be a dalit.”

Despite inheriting Shankar’s legacy and possessions Bahuan loses Maya because of his caste. Her family opposes their marriage because Bahuan is a dalit. The treatment of caste in the telenovela is more complex than caste being a simple hurdle to love. The telenovela attempts to explicate the creation of caste, its functions and lived reality for people of different castes. Class and caste intersect in a curious way for Bahuan who is an upper class dalit educated abroad because he was fortunate to be adopted by Shankar. To contrast Bahuan’s privilege, the telenovela introduces another dalit boy Hari. Although Bahuan is aware of the travails of Hari, Bahuan’s class status conflicts with his caste affiliation and he does not prevent any discrimination against Hari. The telenovela’s exploration of the issue of caste is multifaceted however the primary lens through which the caste plot is constructed is one of Bollywood. It straddles between the simple Bollywood narrative that pits caste as a hurdle the lovers must overcome and more complex Bollywood representations that treat caste as a social problem.

Treating caste as a social issue and problem dovetails neatly with the social functions performed by the telenovela genre (J. Straubhaar 1988) (Porto 2011).

“In the course of its development, the [Brazilian] telenovela started to incorporate an ‘explicit pedagogical action’ that presents itself at a deliberate way, and whose speech brings explanations, conceptualizations and definitions, and finally, it shapes the public opinion about the addressed social themes” (Vassalo de Lopes 2009).

These telenovelas perform an overt pedagogical function by presenting “‘social merchandising’ that brings to the forefront a certain conduct, position and behavioural response to societal questions” (Thomas 2011). For Caminho das Indias’ social merchandising the author Gloria Perez focused on psychic disorders and the social treatment of people with mental disabilities though a couple of minor Brazilian characters Yvone and Tarsus. Tarsus is the son of Ramiro the co-owner of a Brazilian firm Cadore which does business with Raj and Bahuan’s India based ventures. Yvone, is a seductress who entices Raul, Ramiro’s brother also a co-owner of Cadore. Yvone is depicted as a psychopath whereas Tarsus suffers chronic depression. However, for the Indian representation, caste, Indian customs and family ties remained the primary social focus that again emphasizes the telenovela’s Bollywood influence.

Due to its rootedness in oral culture, “Hindi film dramas are we-inflected [i.e. they focus on the collective joint family rather than the individual]… [and] consistently and continuously conserve the traditional order.” (Nayar 2004, 17). A typical Bollywood story therefore privileges parental control over a young couple’s romantic desires. A stereotypical Bollywood storyline is usually about forbidden love.

- The love is forbidden or unrequited due to caste, class or other social differences.[16]

- Generational difference becomes prominent because elders do not understand young love and often present the primary hurdle.

- All these struggles are presented with a healthy dose of melodrama and a happy ending for everyone concerned.

Several of these typical traits hark back to Nayar’s argument about oral roots of India’s cinema and hence the cinema’s communal rather than individual inflection. The films are also “tradition-refining” rather than “originality seeking” a distinction David Bordwell makes when comparing Chinese popular cinema with the west.[17] The term “tradition refining” equally applies to a Bollywood storyline.

Caminho das Indias closely adheres to the stereotypical formula where Maya’s family object to her marriage with Bahuan because he is a Dalit and at the same time Raj is forbidden from marrying his Brazilian girlfriend Duda because she is a foreigner. The two heart-broken souls find comfort in each other as their families lure them into arranged marriages. The generational difference between the old and young become apparent when the elders explain to their belligerent children why an arranged marriage is best suited for them. In a melodramatic scene reminiscent ofIndian soap operas and Hindi films, Raj’s elaborately dressed mom exhorts lord Shiva to “light the wisdom lights” in her son’s head and tells her son that she will fast every Monday till he changes his mind about the Brazilian girl Duda, the foreigner whom he wants to marry. The elaborate costume, sets and profuse melodrama also evoke India’s saas-bahu[18] sagas popularized by Ekta Kapoor.[19]

|

|

| ... her sister-in-law Surya ... | ... is one of the most entertaining evocations of the saas-bahu genre. |

|

|

| Maya confronts Surya. | The two women have a fight ... |

|

|

| ... in the kitchen ... | ... throwing utensils at each other. |

|

|

| Maya throws a plate at Surya. | Surya ducks. |

|

|

| Hearing the ruckus in the kitchen, their father-in-law Opash intervenes. | Opash shows controlled anger of the “patriarch” whereas his wife Indira goes hysterical. |

|

|

| Maya and Surya stop the fight and listen to his chiding. | Opash warns them not to repeat such behavior again or there will be consequences. |

There is a popular adage in Indian culture that when a woman gets married she doesn’t just marry her husband but his entire family. Ekta Kapoor’s soap operas epitomize the adage with heightened drama and melodrama which mostly unfolds in the kitchen and the family living room. The soaps focus on the trials and tribulations of the daughter-in-law as she battles with her vile and malicious mother-in-law and sisters-in-law. In Caminho das Indias the ongoing rivalry between the main female protagonist Maya and her sister-in-law Surya is one of the most entertaining evocations of the saas-bahu genre. Feeling insecure upon the arrival of Maya, the family’s new daughter-in-law, Surya resorts to petty villainy like secretly putting salt instead of sugar in the tea that Maya brews for the elders in the family. She also tells Maya that her husband had an affair with a Brazilian woman and still has feelings for her in order to create a rift between the newly married couple. Maya’s discomfort with Surya builds up and the two women have a fight in the kitchen. They keep throwing utensils at each other until their father-in-law Opash intervenes and threatens to “return” them to their parents.

There are many other instances in the telenovela where similar situations are enacted. Kitchen politics, rivalry among the women in the family and extramarital affairs are at the core of the Indian soap opera genre popularized by Ekta Kapoor which is reenacted in the telenovela. However, the Indian soaps too borrow heavily from Bollywood in terms of aesthetics and stylization as well as music. So there is a transitive relationship between Indian soap opera inspired parts of Caminho das Indias and Bollywood as well.

In sum, Caminho das Indias is a Bollywood-esque narrative where social and family pressures prevail; the protagonists Raj and Maya offer meek opposition to their families when the families try to get their marriage arranged. Upholding tradition is paramount in the story; the telenovela emphasizes the rituals accompanying Indian social life, be it warding off the effects of a Manglik[20] spouse in a hindu marriage or fasting for Karva Chauth.[21] The milieu evoked resembles the colorful India of festivals, marriages and song and dance presented through Hindi cinema.[22] In the telenovela communal values supersede individual desires, another common narrative trope in Bollywood. However the telenovela is different because the episodic nature of the telenovela renders/requires its plotline to be more complicated than a three hour Bollywood feature. Caminho das Indias for instance featured 203 episodes and was telecast in Brazil every week day at prime time from January 2009 to September 2009, the average length of each episode was about fifty minutes. Since telenovelas have a finite story arc yet they are beamed every day, they feature several intermeshing minor storylines within the main narrative. The plot therefore is akin to Ekta Kapoor’s saas bahu (mother-in-law daughter-in-law) sagas on Indian TV that weave similarly intricate plotlines where the married woman’s ex-lover or boyfriend (unable to forget her) keeps reappearing in her life. The social order however, is restored and all the loose ends are neatly tied together when Maya is reunited with her husband Raj.

Locating Bollywood in language

Caminho das Indias abounds with Hindi phrases like “Arrey Baba” (Oh, my goodness), “Bhagwan Ke Liye” (For God’s sake) and hindi words like chalo (let's go) accha (okay), namaste (customary Hindu greeting which means the divinity in me bows to the divinity in you). All these are common cultural phrases heavily used in Bollywood films. Several Bollywood songs begin with the word arrey baba. Ruk Ruk Ruk Arrey Baba Ruk was a popular song from the 1994 Bollywood film Vijaypath and Arrey Baba Arrey Baba Karey Kya Deewana was another well-known song from Auzaar (1997). Bhagwan Ke Liye is another melodramatic phrase that is integral to Bollywood films. Often used to express shock or dismay, Bhagwan Ke Liye amplifies melodrama. Arrey Baba, another popular colloquial term connotes frustration with the situation at hand.

It is evident that Bollywood has been important in the conceptualization and production of the telenovela. There is a self-reflexive acknowledgement and homage to Bollywood in a scene where Maya along with Raj and his family members watch Jodha Akbar in a movie theater and try to mimic the emotions, exuberant celebration and dance enacted on the screen.

The aesthetics and stylization of the telenovela are closely based on Bollywood. The sets closely resemble Bollywood film sets. For instance Maya Meetha performs to the song Tumhari mehfil main aa gaye hain from the 2006 Bollywood film Umrao Jaan for the first time in a setting that is similar to the original. The general appearance and look for Maya Meetha’s character were based on Bollywood actor Aishwarya Rai . Juliana Paes who played Maya in the telenovela asserts that they tried to “find a balance between the everyday life of Indians and the glitz of Bollywood.” However, in the series in the fashion of a typical Indian soap opera “everyone is dressed for a wedding, even if they are just stepping out to the shops or a casual lunch” (Mathur 2009).

Additionally, everything depicted in the telenovela is explained through Bollywood celebrity practice. In order to lend credibility and establish the contemporaneity of her cultural translation of India, Gloria Perez alludes to Bollywood celebrities and their embodiment of those cultural, religious symbols and practices. There are several instances in the narrative of the telenovela, the accompanying authorial voice through Gloria’s blog and the Rede Globo website that substantiate this. In the telenovela the female lead character, Maya, is a Manglik. In Hindu customs pertaining to marriage, astrology is emphasized and being Manglik (i.e. Mars in a particular position in a person’s birth chart) is considered a dosha (flaw) because it indicates difficulties in marriage and marital life. It is believed that the negative consequences of the flaw can be resolved if the Manglik performs a kumbh vivah before their actual marriage. In the kumbh vivah ceremony the person with the Manglik dosha marries a tree or a silver or gold idol of Lord Vishnu, a Hindu deity. The ceremony is said to ward off the negative effects of Manglik dosha. Perez explains the concept and its depiction in the telenovela in her blog using Bollywood celebrity actor Aishwarya Rai’s kumbh vivah[23] as the exemplary instantiation of this Hindu tradition:

“In the telenovela Maya marries a tree, there may be curiosity among you all to go search and understand about Manglik dosha. In India there are thousands of marriages to trees and animals to break the Manglik curse. Indian actress Aishwarya is a “Manglik”, to break her Manglik flaw she married a tree.” (Perez 2009)

Another instance of celebrity embodiment of cultural practices can be found in Perez’s post about Karva Chauth where she mentions Bollywood celebrity Aishwarya again and quotes the actress talking about the religious fast she observes for her husband’s well-being.

Evidently, the author’s translation of India for the telenovela audience is filtered through a Bollywood lens whereby celebrity embodiment provides justification of cultural and religious practices. Bollywood and Indian popular culture in essence epitomize India in the telenovela.

To

top![]() Print

version

Print

version![]() JC 56

JC 56 ![]() Jump

Cut home

Jump

Cut home

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License.