Since the development of the blockbuster model in the 1970s, the major studios have shifted their focus away from stand-alone hits and toward franchises, what Thomas Schatz calls “calculated megafilms designed to sustain a product line of similar films and an ever-expanding array of related entertainment products.”[38] [open notes in new window] U.S. superhero comics, no longer a mass medium crowding newsstands, now provide content for those franchises.

But as Clare Parody argues, we can most usefully think of the “content” that studios adapt not as narrative or even necessarily character, but as “brand identity, the intellectual property […] and presentational devices that cohere, authorize, and market the range of media products that together comprise the franchise experience.”[39] In their big-screen adaptations of these brands, studios turn the policing of intellectual property into a heroic melodrama, a “presentational device” at the center of the “franchise experience.”

But why, readers may ask, do superhero blockbuster fixate so on copying? Why don’t other Hollywood genres worry over intellectual property within their narratives?

From the birth of the comic-book superhero, publishers copied the pattern of successful characters and attacked competitors who copied their own characters, and this work still preoccupies the managers of these brands. Superman first appeared in the June 1938 Action Comics no.1, the sales of which exceeded everyone’s expectations for the still-new medium of monthly comic books filled with original stories (i.e. not just reprints of newspaper strips). It sent publishers scrambling to duplicate its success. Unlike a hit Hollywood movie, a hit comic book required little capital and planning; a few dozen pages of four-color newsprint cost little compared to a knock-off Gone with the Wind.

National Allied Publications, which published both Action Comics and Detective Comics, wanted to duplicate the success of Superman. So Detective Comics artist and editor Vin Sullivan asked Bob Kane to invent another superhero.[40] Kane and his (usually uncredited) collaborator Bill Finger whipped up the Bat-Man, who, like Superman, wore a circus-acrobat costume, had a dual identity, fought antisocial crime, and had special powers (here, martial-arts prowess and the genius to invent gadgets).

But such imitation also crossed lines of company ownership. Jones writes about the lore of this “gold rush.”

“One story passed among creators for years, now presented as fact in nearly every history of comics, concerned a Detective Comics bookkeeper named Victor Fox who saw the sales figures for the first issue of Action Comics, closed his ledger, said he was going to lunch, rented an office in the same building, and that same afternoon announced that he was a comic book publisher. The story isn’t true. Fox never worked for Detective Comics [….] How he heard about the comic book bonanza is unknown, but in late 1938 he appeared to the Eisner and Iger studio and said, ‘I want another Superman.’”

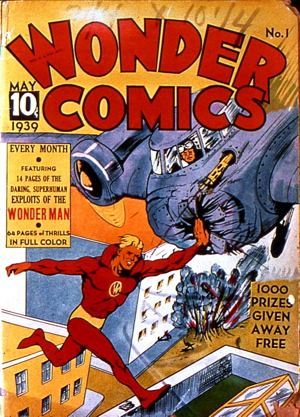

Will Eisner and Jerry Iger ran an independent comics shop, a shop not in the retail sense but the factory sense: a suite of writers and artists who supplied stories on demand to publishers who needed to fill pages. Eisner and Iger’s shop delivered Wonder Man, “a blond, red-costumed superhero with powers duplicating those of Superman” who “had his first and last appearance in Wonder Comics no.1 (May 1939).”[42] National immediately sued Victor Fox for infringing their copyright on Superman.

In his 29 April 1940 opinion in the case of Detective Comics, Inc., v. Bruns Publications, Inc., et al., Judge Learned Hand notes three ways that Wonderman copies Superman. Wonderman styles its star “champion of the oppressed,” as Action Comics styled Superman; Wonderman possesses preternatural strength and immunity to firearms; and Wonderman “at times conceals his strength beneath ordinary clothing” only to reveal “a skintight acrobatic costume” beneath.[43] Hand’s opinion also cites two precedents, Sheldon v. Metro-Goldwyn Pictures Corporation and Nichols v. Universal Pictures Corp.[44] Hand’s citation of Hollywood precedents tells us something important about the relation between intellectual property and industrial practice: since at least 1940 comics publishers and Hollywood studios have influenced one another, exchanging not just content to remediate but also legal precedents, a body of intellectual property law that regulated the two industries long before conglomeration brought them together. The ground on which 21st-century studios build new superhero narratives consists of sedimented layers of innovation, duplication, and managerial anxiety about intellectual property.

The pedagogical blockbuster

Superhero movies became major studio business during a period of explosive growth in home video sales between 2002 and 2007, a period that Billboard, Retailing Today, Variety, Video Business, and the Wall Street Journal called the DVD boom. During the boom, DVD retail became the “the largest source of consumer spending on filmed entertainment across all distribution channels.”[45] By 2007, theatrical exhibition supplied only 21.4% of Hollywood’s revenues, while home video supplied 48.7%. [46] In order to protect their revenues, the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) pursued a campaign to reduce the unauthorized copying of video. One public aspect of that campaign resulted from the partnership between the MPAA and the Intellectual Property Office of Singapore (IPOS).

The IPOS launched a public-relations initiative called “Honour IP,” shortened to “HIP.”[47] From this partnership resulted a trailer, “Piracy: It’s a Crime,” which then screened in Singapore before House of Flying Daggers (Zhang Yimou, 2004). A techno score pounds over a montage of thefts shot with speed-ramping and breakneck zooms, as intertitles in a distressed font hail the viewer:

“You wouldn’t steal a car. You wouldn’t steal a handbag. You wouldn’t steal a television. You wouldn’t steal a movie. [Here, a shoplifter steals a DVD.] Downloading pirated films is stealing.”

The MPAA then made this trailer available for U.S. DVD manufacturers, who put it on discs before movies. Manufacturers added a feature that angered buyers: viewers could not skip this propaganda film. “Someone really wants you to watch this,” wrote Finlo Rohrer, covering the backlash among DVD buyers.[49] Parodies of the trailer became an online meme, subverting the IPOS’s goal of making their anti-copying position hip.

In a bit of unintended farce, the makers of “Piracy: It’s a Crime” had used music by Dutch artist Melchior Rietveldt, but they had told Holland’s music royalty collection agency, Buma/Stemra, that the trailer would run only “at a local film festival.” Rietveldt later discovered his own music playing in the trailer on a Harry Potter DVD.[50] Worse, when Rietveldt complained to Buma/Stemra, one of the agency’s officers offered to help him sue for royalties on the illegal condition that Rietveldt give the officer a third of any settlement that Rietveldt obtained.[51] According to court documents from Rietveldt’s ensuing lawsuit (which he won), the trailer ran on “at least 71” different DVD titles.[52]

“Piracy: It’s a Crime” falsely conflates copying with various kinds of stealing. Unlike a thief who steals one of my belongings, an unlawful copier does not deprive me of my use of the thing copied. Copying only deprives me of a possible future “use” if I have a limited monopoly on the reproduction of the thing in question. Crucially, such a monopoly does not depend on my having made the thing. Singapore’s Senior Minister for State and former law professor Ho Peng Kee said of the “Honour IP” campaign,

“Whether it is a fancy gadget, a household brand or music and movies, someone invested time and effort to create it and owns the intellectual property in it. We need to realise that it takes numerous parties working endless 18-hour days to bring to us a unique piece of movie magic.”[53]

Ho pays lip service to the labor that goes into media production while obscuring the legal relations that exclude most workers from a share in the profits their work generates.

Below-the-line workers directly benefit from intellectual property laws only if they have organized to bargain for a share of residual profits, and then only according to the terms that they negotiate. Hollywood labor unions have collective bargaining agreements that require studios to pay residuals from movie profits to unions not in individual compensation, via payroll, but in payments to the Motion Picture Industry Pension and Health Plans.[54] The Screen Actors Guild secured these agreements in 1960 (ironically, under Ronald Reagan’s leadership).[55] Changes in the locations of production and in the profitability of distribution platforms mean that such agreements come under re-negotiation, as seen in the 2007 strike by the Alliance of Canadian Cinema, Television, and Radio Artists (ACTRA) over the terms of compensation for digital media residuals with U.S. studios.[56] Workers not represented by unions receive no share in the profits from the intellectual property they create, whether they work in Los Angeles, Vancouver, or at the new Oriental Movie Metropolis in Qingdao. Some might argue that media franchises dependent on existing intellectual property constitute long-term projects that require future labor to keep running, and that therefore intellectual property laws indirectly benefit workers hired by those franchises, but this amounts to saying that those who work for a living benefit from having the chance to be exploited by those who merely own.

Unlike many workers in the U.S. film industry, including cartoon animators, comic book artists failed to organize into unions.[57] The freelance and work-for-hire contracts under which the great majority of comics artists have worked shut them out of participation in the profits from their work. When the Copyright Act of 1976 took effect, it solidified the legal basis for artists to claim sole copyright to their work, but as Paul Lopes notes, “a loophole in the act exempted ‘work-for-hire’ artists from these rights,” such that “DC and Marvel immediately made up new contracts and release forms that designated artists as work-for-hire artists.”[58] These contracts shield publishers and studios from sharing profits with labor.

Supplementing the pedagogical project of implicitly pro-shareholder texts like “Piracy: It’s a Crime” we find the narratives of superhero blockbusters that position copycats as villains. In Superman IV: The Quest for Peace (Sidney J. Furie, 1987), Lex Luthor cloned Superman against his will, but we would not see the trope return to the screen until the DVD era, when piracy and torrenting became such worries for studios. In a parody of Copyleft or Creative Commons activism, these films present illicit copiers as fools at best, genocidal sociopaths at worst.

“A fair, efficient, and predictable environment”

Marvel’s Iron Man films contain a paradox: Tony Stark invents technology that should radically change human civilization, but each film begins in our familiar world, not changed by flying armor or clean energy. This becomes most apparent in Iron Man II (Jon Favreau, 2010). Early in the film, Tony Stark testifies to the U.S. Senate Armed Services Committee about the Iron Man armor in a set-piece that shows director Favreau and his actors in top comedic form while also making the case for private control of the armor. A senator named Stern declares, “My priority is to get the Iron Man weapon turned over to the people of the United States of America.” Yet Favreau’s casting of Gary Shandling as the senator telegraphs to viewers that we should not take this stern and pompous man seriously. Favreau’s casting of Sam Rockwell as the smarmy, incompetent defense contractor Justin Hammer, CEO of Hammer Industries, helps render Hammer as the farcical, Louis-Napoléon inverse of Tony Stark.

Stark’s sidekick, Lieutenant Colonel James Rhodes, played with confidence and grace by Don Cheadle, testifies regarding attempts by Iran and North Korea to develop their own versions of the Iron Man armor. He presents satellite photos of the test sites. Stark interrupts Rhodes’s testimony, using his super-smartphone to hack the room’s computer system; Stark then shows the committee footage taken on the ground by the foreign governments. The North Korean armor malfunctions, spraying bullets among onlookers, and the Iranian suit explodes. Finally, in a video bearing the Hammer Industries logo, Justin Hammer appears beside another malfunctioning suit. “I’d like to point out that that test pilot survived,” says Hammer.

By hacking the monitors to show these failures, Stark demonstrates technological mastery, not just compared to competitors but also compared to the U.S. government, whose intelligence he bests and whose equipment he hacks. “You want my property? You can’t have it!” he says. “I have successfully privatized world peace.” Stark, already a billionaire, need not sell his technology, even to the state.

While this sounds like a neoliberal dream, Iron Man II’s narrative presents the “private” element of privatization as a fragile ideal requiring defense. The film pits Stark against an alliance between copycat Hammer and Russian genius Ivan Vanko (Mickey Rourke). Vanko develops not only a suit of powered armor but also a fleet of drone suits for Hammer Industries. In the film’s climax, Stark confronts something like a capitalist’s nightmare: the proprietor finds his own intellectual property turned against him, the alienator now the victim of alienation. Stark defeats the drones and Vanko, such that the film gives Capital a happy ending, but Labor doesn’t get one. Even in the interior shots of Justin Hammer’s factories, workers rarely appear, and when they do, they appear far in the background, out of focus.

Iron Man II frames Stark’s rivals and the state as neither ethical enough to trust with the armor nor competent to duplicate it. Only Vanko, motivated by a personal (and therefore non-commercial) grudge, has the necessary ability, but his defeat in the film’s climax ends his competition with Stark. The Avengers (Joss Whedon, 2012) and Iron Man III (Shane Black, 2013) therefore take place in a world without ubiquitous flying armor or miniature fusion reactors. Stark thus protects the world by protecting his intra-diegetic monopoly on what Marvel Studios would call “the Iron Man business.” Within the diegesis, the hero creates intellectual property, while outside the diegesis, corporations sell and license the hero as intellectual property.

Of all superhero films, the Iron Man franchise shows the most sustained interest in recent U.S. military interventions overseas. The first film in the series re-writes the hero’s place of origin from Vietnam to Afghanistan, into the context of Stark Industries’ sale of weapons to U.S. clients in the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan; the third film pits the hero against a terrorist organization seemingly based in Muslim countries, which exploits veterans of recent U.S. occupations. Neither this superhero movie franchise nor any other sends its hero to Iraq, the most bloody and least popular U.S. intervention since Vietnam. Studio executives showed instrumental rationality in avoiding even the appearance of taking a side that might provoke opposition from potential viewers.

Yet if the U.S. occupation of Iraq constitutes a subtext of Iron Man’s adventures, then U.S. attempts to rebuild Iraq along lines favorable to multinational corporations therefore constitute a subtext of the 21st-century superhero film genre’s obsession with intellectual property. As superheroes battled would-be copycats on the screen and MPAA trailers equated copying with theft, the Coalition Provisional Authority, installed in Iraq by U.S. military force, proclaimed a set of legal and economic reforms known as the 100 Orders. Order 80 aimed to secure intellectual property, because “companies, lenders and entrepreneurs require a fair, efficient, and predictable environment for protection of their intellectual property.”[59] The language suggests neutrality, but the Orders set the stage for the privatization of Iraqi industry and resources by foreign corporations

Like Justice Kennedy’s 2010 opinion in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, Order 80 says nothing about structural imbalances of power or wealth. For Kennedy, corporations merely represent “associations of citizens,” and laws that restrict corporate spending (here equated with speech) unfairly discriminate against a category of those associations.[60] Like the Intellectual Property Office of Singapore, the Coalition Provisional Authority uses language that obscures the economic relations that it actually promotes. Order 80 instead frames the need to protect intellectual property in populist terms, “as necessary to improve the economic condition of the people of Iraq.”[61] In May of 2003, Paul Bremer announced, “Iraq is open for business again.”[62] As many critics of the occupation pointed out, Bremer meant a particular kind of business: that of multinational corporations.

Wendy Brown notes that Iraqi farmers had long obtained seed “from a national seed bank […] in Abu Ghraib, where the entire bank vanished after the bombings and occupation.”[63] Into this void stepped foreign agribusiness, who could now, under Order 81, apply for “plant variety protection” for genetically modified seeds.[64] Nancy Scola says that Bremer’s announcement amounted to “telling Monsanto that the same conditions had been created in Iraq that had led to the company’s stunning successes in India.” [65] Scola reminds us that hundreds of Indian farmers bankrupted by their dependence on Monsanto seeds committed suicide by drinking the company’s Round-Up herbicide. She also notes that genetically modified seeds contaminate the larger gene pools of related crops, such that “eventually much of the world’s seeds could labor under patents controlled by one agribusiness or another.”[66]

|

|

| Justin Hammer congratulates himself in Iron Man II (Marvel Studios, 2010), not realizing that genius villain Ivan Vanko has used him as a stooge. | Only Ivan Vanko (Mickey Rourke) has the brilliance to equal Stark’s designs in Iron Man 2 (Marvel Studios, 2010), such that Stark and Rhodes, the private-sector hero and his public-sector sidekick, must work together to defeat him. |

|

|

| The GM super-plant smolders, ready to detonate in Iron Man 3 (Marvel Studios, 2013). | Maimed veterans become raw materials for a pro-active disaster capitalist in Man 3 (Marvel Studios, 2013). |

Lest we think that Monsanto would not use such a scenario for their benefit, Monsanto has refused to pledge not to sue farmers who claim that Monsanto seeds have colonized their stocks. The company declared,

“A blanket covenant not to sue any present or future member of petitioners’ organizations would enable virtually anyone to commit intentional infringement.”[67]

Genetically modified plants propagate independent of farmers’ volition, colonizing non-proprietary seed stocks, much as corporate media brands can propagate spontaneously through social networks of fans.[68]

Iron Man III departs from its precursors’ fixation on the copying of the Iron Man armor, but its narrative focuses on intellectual property in a way even closer to the neoliberal geopolitics of the 2000s. The first hint about the true nature of the villain appears in the form of a genetically modified plant that, when damaged, first regenerates and then explodes. The second hint appears in the spontaneous combustion of returning U.S. military veterans. These veterans have volunteered as test subjects for a mad-scientist-entrepreneur’s experiments in the hope of recovering limbs they lost in war. “I’ll own the War on Terror,” crows the villain. “I’ll create supply and demand!” He plans to monetize the cycle of US military intervention: using his biotechnology, a bogus “terrorist” network will strike targets worldwide, while he sells biotechnology to the U.S. military to regenerate maimed soldiers.

|

|

| Advanced Idea Mechanics (AIM) conducts tests on maimed American veterans in Iron Man 3 (Marvel Studios, 2013). | A mysterious terrorist calling himself “The Mandarin” claims responsibility for apparent suicide bombings on US soil in Iron Man 3 (Marvel Studios, 2013). His video montages threaten ever greater carnage. |

|

|

| On of the AIM test subjects explodes outside TCL Chinese Theatre in Iron Man 3 (Marvel Studios, 2013), in an attack mistaken for a suicide bombing. This setting seems unmotivated unless one knows that the Huizhou-based TCL Corporation, one of the world’s largest manufacturers of televisions, bought naming rights to the Chinese Theatre a few months before the release of Iron Man 3. | The film’s many attempts to reach the Mainland Chinese theatrical market also include changing the nationality of the Mandarin from Chinese (as in the comics) to American. In Iron Man 3 (Marvel Studios, 2013), the villain hires a drugged-out British actor (Ben Kingsley) to play his fake terrorist mastermind, “The Mandarin,” in threatening TV broadcasts. |

|

|

| “I’ll own the War on Terror,” declares terror-preneur Aldrich Killian (Guy Pearce) in Iron Man 3 (Marvel Studios, 2013). | The “real” Mandarin, and the film’s true villain, reveals Chinese-dragon tattoos in the climax of Iron Man 3 (Marvel Studios, 2013). |

The villain of Iron Man III thus presents a comic book version of what Naomi Klein has called “disaster capitalism,” using and even engineering large-scale destruction to create commercial opportunities.[69] Like the neoliberals who rebuilt occupied Iraq for corporations, the villain of Iron Man III does not disdain state power. Unlike an Objectivist or an “anarcho-capitalist” he requires the state’s intervention even as he subverts its purposes.

While Iraq represents an extreme example of the re-structuring a country’s legal order for the benefit of corporations, it differs in tactics but not in strategy from Disney’s intervention to promote the 1998 Copyright Term Extension Act (CTEA), which gave corporations an additional twenty years of rights to their intellectual property. The CTEA extended copyrights of individual works, but it also extended copyrights of corporate works—like those produced under the work-for-hire agreements at DC and Marvel—from seventy-five to ninety-five years after first publication.[70] Disney, as Wasko notes, “provided campaign contributions to ten of the 13 initial sponsors of the House bill and eight of the 12 sponsors of the Senate bill.”[71] Without the CTEA, “Golden Age” comic-book characters like Captain America, the Human Torch, Batman, Superman, and Wonder Woman would already have fallen into the public domain.

Critics of the CTEA call it the Mickey Mouse Protection Act, noting that every time copyright on the Mouse nears expiration, Disney and other powerful intellectual property holders lobby Congress to extend their claims. Derek Khanna, making what he calls “The Conservative Case for Taking on the Copyright Lobby,” writes,

“The recapture of works that would be in the public domain represents one of the biggest thefts of public property in history.”[72]

Intellectual property law scholar Chris Sprigman calls out the owners of DC and Marvel by name:

“The only reason to extend the term is to give private benefits to companies like Disney or Time Warner.”[73]