The “Affaire Jutra” and

the figure of the child

On the shoot of La Dame en couleurs [My Lady of the Paints]:

Jutra’s troubling proximity to children.

i. The Jutra Affair

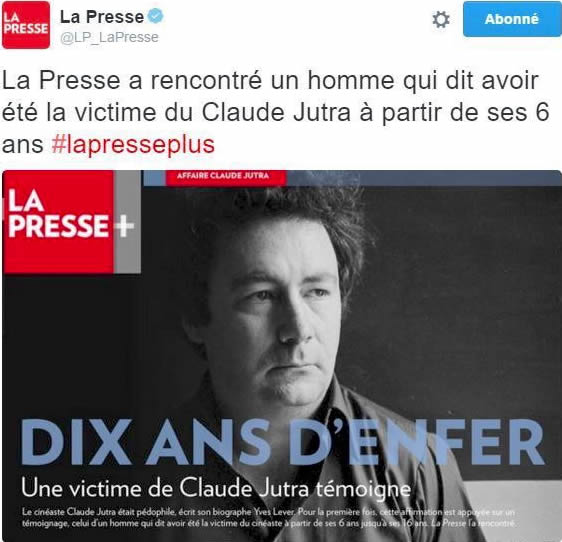

On February 13, 2016, the advance publicity for Yves Lever’s biography of iconic Quebec filmmaker Claude Jutra dropped a bombshell: Several individuals interviewed for the book claimed to have been victims of Jutra’s sexual advances as children or teenagers. Lever’s allegation that the filmmaker had been a pedophile unleashed a highly mediated scandal in the Quebec arts scene. At first, several well-known commentators expressed indignation at this black mark on Jutra’s reputation on the basis of anonymous allegations thirty years after his tragic suicide. For instance Lise Payette, the legendary journalist and politician, vehemently rejected Jutra’s “execution at dawn.” Yet despite numerous passionate defenses by key cultural figures, the scandal that came to be known as the “Affaire Jutra” (the Jutra Affair) was not so easily dissipated. On February 17, Montréal daily La Presse published the anonymous testimony of a man given the pseudonym “Jean” describing his sexual abuse over a decade from the age of six at the hands of Jutra, a friend of the family (Pilon-Larose).

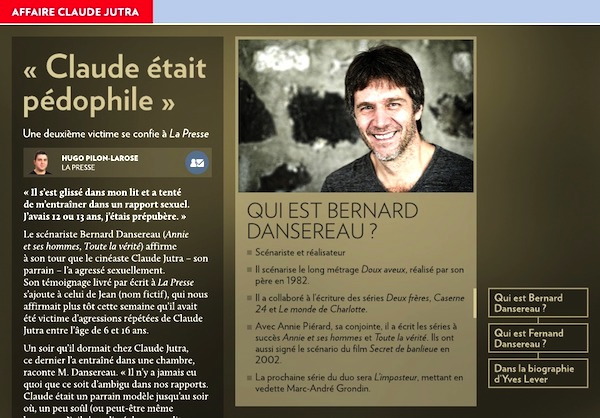

That same day, the Québec government and arts community made three extraordinary announcements: The Ministère de la culture et des communications and Québec Cinéma announced that Jutra’s name be stripped from the province’s annual film awards, and the Canadian Screen Awards withdrew Jutra’s name from its award for Best feature by a first-time director. Also, Further, the Cinémathèque québécoise announced its decision to change the name of its main screening room that had born Jutra’s name since he presided at its inauguration in 1963. Finally, all streets and squares named for Jutra across the province were renamed on the authority of the seven municipalities concerned, with the support of Québec’s Commission de toponymie. These decisions were taken solely on the basis of anonymous allegations, three days before screenwriter and director Bernard Dansereau was the first and only person to speak on the record of rebuffing a sexual advance by Jutra, his godfather, at the age of 12. On Feburary 23, news outlets announced the vandalism of the sculpture “Hommage à Claude Jutra” by renowned sculptor Charles Daudelin; the sculpture was later boxed up, removed from the park and put into storage. It is as if this filmmaker who had so vividly marked the cinema of the Quiet Revolution and the Quebec collective imagination was erased from public memory in the matter of a few days.

The rapid erasure of all official public references to Jutra as an iconic cultural figure profoundly destabilized the province’s cultural establishment and the broader Québec society. Why did this posthumous scandal surrounding a filmmaker who has been dead for over thirty years spark a national crisis? While this scandal is in some ways reminiscent of scandals surrounding Michael Jackson, Woody Allen or Roman Polanski, let me point to several salient aspects of the Jutra affair. First, no formal accusation has ever been made against Jutra, who has been dead since 1986.[1] Also, the victims of the filmmaker’s alleged abuse were boys, and I can only speculate about how the factor of queer sexuality fanned the flames of a scandal that was significantly media-driven. Finally, Jutra is widely recognized as a founding figure of a “new wave” of Quebec national cinema closely linked to the incomplete project of forging a distinct Québécois cultural identity.

It is not a simple thing to tease out the delicate symbolic and ethical stakes of the Jutra affair. Many Quebec cultural figures and intellectuals have remained loyal to Jutra’s memory, helping to ensure that the scandal has not affected public access to his works, at least in the short term. In the medium to long term, however, the stigma of “pedophilia” may affect Jutra’s standing in Quebec and Canadian film canons. What is at stake with the Jutra affair for Quebec society, I argue, is more oblique and more profound than censorship. These allegations bring together on the one hand the visceral taboo concerning intergenerational sexual relations and on the other a cultural figure intimately linked with the Quiet Revolution as a point of origin for a modern, secular Quebec. In my broader argument, I analyze the myth surrounding the filmmaker in order to probe the resonance of the Jutra affair in Quebec. Drawing on theories of queer time and the queer child, I examine how the filmmaker’s ambiguous proximity to children across his life and works troubles developmental narratives of masculinity, sexuality, and the nation.

This political cartoon shows the sculptural homage to Jutra and the filmmaker’s many awards being unceremoniously thrown off the Jacques-Cartier Bridge in Montréal. Note that Jutra committed suicide by jumping off this same bridge in 1986.

First, however, I want to take a considered position in relation to the ethical and political dilemmas of the Jutra affair. When Lever first went public with his allegations, I was inclined to read the scandal sceptically as a media stunt to boost book sales. Like many others, I felt that official responses to anonymous allegations were hasty and draconian, whereby government and cultural institutions distanced themselves from what Gayle Rubin calls “bad, abnormal, unnatural, or damned” sexuality. For instance, on February 15, Québec Cinéma had appointed a comité des sages (committee of the wise)[2] to deliberate on Lever’s allegations, only to take a harsh decision on February 17 without awaiting the committee’s findings. In a letter to the editor of the daily Le Devoir published eight months later, these four intellectuals compared the rapid official responses to a spring cleaning: “With one great sweep of the broom, it became essential to make Jutra and his works disappear once and for all.” Not only were these decisions taken far too rapidly, they argued, but no action was taken by the Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux (Ministry of Health and Social Services) to reinforce or make public contemporary public policies related to sexual abuse (Coupal, Binamé, Aubut and Villemure).

Let me return to the evidence contained in the 2016 biography. Lever mentions that many people in Jutra’s entourage refused to talk to him about the filmmaker’s sexuality, and that others insisted on a predominant attitude of “live and let live” in the 1960s and 1970s. However, Lever mentions that several interviewees attested to Jutra’s privileged relationships with boys younger than eighteen that were not merely platonic; the biographer also mentions rumours that teenaged boys involved in the shoot of Mon oncle Antoine had “special” relationships with the director, and that one handsome young actor became Jutra’s “official” lover for several years (153). This is the evidence published in the biography that leads Lever to label Jutra a “pedophile.” Lever excludes the ages of the boys as well as the circumstances of assumed sexual contact between Jutra and minors, perhaps to protect his sources. There are grey zones, I believe, when it comes to relationships between teenagers and adults, and my point of view is shared by several commentators. Film critic Monica Haim for instance counters what she calls the “lynching” of Jutra, with the key point that the age of consent in Canada from 1892 until 2008 was fourteen. Also, actor Marc Béland who had lived with Jutra for two years initially defended what he saw as consensual sexual relations between the filmmaker and young teenagers who would come to the door to seek out the filmmaker: “It was his life … And it’s no one else’s business until someone comes forward to make an accusation if he has been abused” (“Révélations”). [2a] Béland later retracted his defense in light of the subsequent testimonies by “Jean” and Bernard Dansereau.

Game-changing testimonies published in the Montréal daily La Presse: anonymous victim “Jean” attests to “Ten years of hell,” and Bernard Dansereau reveals how Jutra “slipped into his bed” when he was 12 or 13.

For me and for many others, the most serious allegations came from “Jean” who presented a detailed anonymous account of a decade of sexual abuse from the age of six, and Bernard Dansereau’s brave decision to speak on the record. Queer or sexual libertarian perspectives, including the arguments put forward by Tom Waugh and John Greyson in this special section, offer important critiques of moral panics. Yet as a queer thinker who is also a feminist, I weigh the dangers of sexual intolerance against the very real spectre of harm and the difficulties of speaking out about sexual assault. In Québec and elsewhere the feminist movement has played a crucial role in challenging the silences surrounding sexual violence of all kinds and its banalization, and in bringing to light its lasting traumatic effect. In an account that aligns all too well with other cases of childhood sexual abuse, “Jean” also recounts how his schoolwork was affected at the time, and how he later suffered from alcoholism and depression as an adult. When asked by a journalist why he had not spoken to his family about the abuse, the witness’s response was more than plausible: “It was probably because of the name ‘Jutra’ and all that it represented. I didn’t feel able to break all that” (Pilon-Larose). Here, “Jean” evokes the veritable aura surrounding Jutra, a renown that could well have contributed to the filmmaker’s powers of persuasion. The day after “Jean’s” anonymous testimony, Lever stated on the radio that he knew of two other children who had similar experiences with Jutra over shorter time-frames, but that they had not suffered the same devastating long-term effects as “Jean” (“Affaire Jutra”).

As a queer and feminist mom, I am sensitive to children’s eroticism, their sensuality and sexual curiosity, and the importance of facilitating a confident and curious relation to sexuality. I am also attuned to the tremendous trust that children place in adults, a trust that along with their dependence on us leads to their incalculable vulnerability. Audre Lorde has influentially pointed out the power of eroticism as a “resource” for women, but also the damage that comes with the exploitation or misnaming of this “depth of feeling” that she sees as the crux of the life force. While of particular significance to women, Lorde’s account insists on the vital importance of an autonomous sexuality for each person. In this light, we can grasp something of the damage evoked by “Jean” when he states that that “Jutra was the first one to touch me, even before I discovered sexual pleasure for myself” (cited in Pilon-Larose). As with gender relations, intergenerational relationships are framed by social pressures and relations of power and desire. These dynamics place adults – parents, teachers, family friends and relatives, mentors and baby-sitters – in positions of authority and in privileged proximity to children. For me, with this proximity and authority comes an absolute ethical responsibility to respect each child’s emotional and physical integrity. Even as I am outraged for the many women who have suffered sexual violence, I am outraged for “Jean” among many young people who have suffered sexual abuse at the hands of Jutra and others.

This ethical position could lead me to join those who would erase, or at the very least challenge Jutra’s memory as a cherished symbol of the cultural effervescence of the Quiet Revolution. However, I am also wary of the horrors committed “in the name of the child.” I choose to contribute to a considered public debate in order to break the deadlock between a retrospective moral panic on the one hand and on the other the disavowal of any harm caused by Jutra founded on the sanctity of the artist or a sexual libertarian ethic. In the two-part analysis that follows, I first develop a queer reading of the potent myth surrounding Jutra in order to trace why this scandal so deeply disturbed cherished discourses of Quebec culture and nation. Next, I turn to the polysemic figure of the child at the heart of the Jutra affair, attending to the multiple discourses and framings of children and youth in several key films.

ii. The Jutra myth: failure and arrested development

A history of the present

In this section, I present a myth that developed throughout Jutra’s brilliant and uneven career, gaining momentum after the filmmaker’s tragic early death in 1986. Jutra is remembered as a multi-talented child prodigy who has been retrospectively constructed in journalistic and scholarly discourses as Québec’s first genuine auteur, a leading figure in a modern national cinema. Jutra’s career spanned the crucial historical period bridging the end of what is known as the Grande noirceur (the Great Darkness) and the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s and early 1970s. The Quiet Revolution was a period of tremendous cultural and political effervescence marking Québec’s belated entry into modernity. Jutra was the most visible of a group of talented filmmakers who founded a “new wave” of modern Québec cinema from the late 1950s. In order to grasp the resonance of the Jutra myth, it is important to understand that the development of an autonomous postcolonial Québécois cultural identity has been seen as the lifeblood crucial of Québec’s aspirations for sovereignty (Weinmann 1991, Poirier).

This heady historical period also corresponds with the sexual revolution in Québec associated with a refusal of the sexual and social norms imposed by the Catholic Church that had dominated Québec society from the colonial period. Alongside the sexual and Quiet revolutions, Québec second wave feminism and lesbian and gay liberation emerged at the end of the 1960s. The myth of Jutra is closely bound up with a widespread contemporary understanding of the Quiet Revolution as a founding decade for modern Québec society, a social democratic and sexually liberated society. If Jutra has in some ways come to embody the cultural dynamism and creativity of the Quiet Revolution, he has also been read by some as a courageous pioneer of gay liberation. Notably, Tom Waugh identifies the first fleeting glimpse of same-sex desire on Québec screens with Jutra’s 1963 À tout prendre [All Things Considered or Take It All] with Jutra’s confession “I love boys” (see the analysis of this pivotal sequence in the essays by Rodríguez-Arbolay Jr. and Waugh in this special section). On a queer reading, this early pre-liberation sequence is a remarkable exception that proves the rule in a cinema constrained by Catholic morality, censorship and homophobia. Despite the absence of explicit homosexuality in Jutra’s subsequent filmography, Waugh reclaims Jutra as an “ancestor, enigma and martyr of lesbian and gay cinema in Canada” (437).

Reading back from a present so indelibly marked by the Jutra affair, I develop a genealogical reading of the shifting myth of Jutra, who has been consistently framed as an allegory of the tremendous promise and failure Québec’s socio-political and cultural “coming of age.” Foucault’s concept of genealogy proposes a historiographical inquiry informed by the dilemmas and the emergencies of the present. Genealogy involves a refusal of origin, continuity and linear causality, proposing instead to

“follow the complex course of descent” that implies “maintain[ing] passing events in their proper dispersion; identify[ing] the accidents, the minute deviations … the errors, the false appraisals, and the faulty calculations that gave birth to those things that continue to exist and have value for us” (Foucault 146).

This genealogical refusal of origins informs my choice to structure this essay as an encounter between several distinct yet complexly interrelated “courses of descent” that feed into the changing myth of Jutra’s life and works that coincide with multiple “origins”: a distinct postcolonial cultural identity and the unfinished emergence of a sovereign modern nation; a trajectory of feminist and gay and lesbian liberation often associated with the ideal of the modern progressive Québec; and finally, changing socio-historical discourses around children and youth.

Jutra hosts the Radio-Canada television series Images en boîte (1954).

I argue that in toppling this iconic figure of origins from his pedestal, the 2016 Jutra affair called into question several foundational myths associated with the emergence of modern, secular Québec society. I deploy genealogical inquiry and theories of queer time to probe how Jutra as a queer figure troubles a linear account of the unfinished emergence of Québec modernity from the Quiet Revolution. Let me now turn to the peculiarly cinematic figure of Jutra, who has been consistently framed as an allegory of the tremendous promise and failure Québec’s socio-political and cultural “coming of age.”

The Jutra myth

“Claude Jutra was cinema. He was at once 24 images per second and poetry (PIERROT DES BOIS), he was montage, the very essence of cinema (LES ENFANTS DU SILENCE), he was sensitivity and poetry, he was shot, frame and creativity, he was a dictionary of cinema (IMAGES EN BOÎTE), he was at once a man of science and a man of letters, he drew and painted like an artist, he wrote like a poet” (Brault, my translation).

This powerful statement by Michel Brault captures something of the romantic myth of Jutra as a cinematic genius and a Renaissance man. Brault’s account as only one of many homages to the filmmaker published in a commemorative issue of Copie zéro after Jutra’s death.

Born in 1930, Claude Jutra was a trained actor, screenwriter and director, and an accomplished visual artist. He completed his first film Le Dément du lac Jean-Jeunes (1948) at 18, and year later his experimental short Mouvement perpetuel [Perpetual Movement](1949) won the prize for Best Amateur Film at the Canadian Film Awards. The son of a well-known doctor, Jutra had a privileged childhood and studied to become a qualified doctor, but chose to turn to filmmaking instead. As a young man, Jutra was active in the first “Golden years” of Québec public television as a screenwriter, director and host of a series about cinema entitled “Images en boîte” (1954). A member of the National Film Board of Canada’s legendary équipe française (French unit), he participated in many documentaries including La lutte [Wrestling] (1961), Comment savoir [Knowing to Learn] (1966), and Wow (1969). In 1957, he starred in the short pixillated film Il était une chaise [A Fairy Tale], which he co-directed with animation legend Norman McLaren. In a career that coincided with direct cinema, the U.S. avant-garde, the French New Wave, and European art cinema, Jutra collaborated with legendary European cultural figures including Jean Cocteau, Bernardo Bertolucci, Jean Rouch, and François Truffaut. Finally, Mon oncle Antoine, Jutra’s most critically and commercially successful feature won numerous awards and has become a classic of Canadian and Québec cinema.

Jutra’s early successes were offset by a series of personal and professional disappointments and failures. Partly self-financed, his first feature À tout prendre was a critical and box-office flop at the time of its release in 1963, and Jutra was left bitter and burdened with debt. If Mon oncle Antoine [My Uncle Antoine] (1971) marked the pinnacle of his career, Jutra’s next two films were also critical and commercial failures: the costly and much anticipated Kamouraska (1973) starring Geneviève Bujold and Pour le meilleur et pour le pire (1975). Unable to find funding for his films in Québec, this committed sovereignist was forced to work in English Canada from 1976. In his discussion of the Jutra myth, Mario Patry describes what came to be known in Québec as Jutra’s “exile” to English Canada:

“Unable to find work in 1975 after never having earned more than $9,000 during the 1970s (while a filmmaker employed at the NFB earned $12,000), his exile sounded the death knell for the Québec film industry” (17).

Jutra also faced personal difficulties that were woven into his ever-evolving myth, including a nearly fatal scooter accident on the Jacques-Cartier Bridge in 1967. In the last years of his life, Jutra returned to Montréal where he lived in relative poverty and had trouble working due to Alzheimer’s. A life and a career that had begun so brilliantly ended tragically. Jutra disappeared on November 5, 1986, and his body was only found the following spring on the banks of the St Lawrence River down river from Montréal. Leach argues that while Jutra’s suicide was most logically related to his struggle with Alzheimer’s,

“this explanation did not completely allay suspicions that he had been worn down by the constant struggle to make films in an unsupportive cultural climate” (5).

|

|

| Jutra’s fascination with water: Young man on a bridge in Mouvement perpetuel (1949) and the dénouement of À tout prendre. | |

Crucial to the myth that crystallized after Jutra’s death is an extraordinary cross-fertilization between personal experience and cinematic images. Jutra’s suicide by drowning after jumping off the Jacques-Cartier Bridge was prefaced by a career-long fascination with water, including several cinematic rehearsals of men falling into water froma height (Le Dément du Lac Jean-Jeunes, Mouvement perpetuel). Most famously, in the dénouement of À tout prendre, Jutra, playing a version of himself, deliberately walks off the end of a dock into a river. In the film’s closing sequences, Claude’s friends search everywhere for their missing crony, asking each other: “Have you seen Claude?” The animated short Jutra, part of an extensive media archive surrounding the filmmaker, returns to this moment.

MISSING: a frame from Marie-Josée Saint-Pierre’s remarkable animated and compilation film Jutra (2013). This film can be streamed for free from the NFB website at: https://www.onf.ca/film/jutra_fr/

Jutra’s tragic later years and his death by suicide fuelled a posthumous myth surrounding the filmmaker. A revisionist return to À tout prendre, his most personal and ambitious auto-fiction, contributed to this process. With its scandalous references to adultery, interracial sexual relationships, abortion and homosexuality, À tout prendre was released to mixed reviews in a conservative Québec society in 1963. Most critics agreed on Jutra’s extraordinary potential, originality, innovative technique, and his “talent fou” (extraordinary talent). At the same time, the film was critiqued as being too personal, as narcissistic, and as privileging technique over substance. Interestingly, few reviewers directly address the film’s coming out sequence, evoking instead its “moral strip-tease” and its unfashionable focus on a bourgeois “bohemian” milieu. Finally, several critics described À tout prendre as a promising yet “immature” or “adolescent” work, keenly anticipating Jutra’s “mature” films to come (Basile).

Out of circulation for a number of years, À tout prendre was later reassessed by critics. For instance, in 2000 Jean Chabot heralds À tout prendre as “the first great film of personal expression produced in Québec”:

“In a society still dominated by the image of saint Joseph, who has become an emblematic figure for the nation Jutra made a resounding statement. He said: ‘I am a bastard.’ He said: ‘I am something other than what the discourse of national survival wishes me to be or remain. I am searching for a different ethic’” (Chabot 25-26).

Here, Chabot reclaims À tout prendre as a prescient masterpiece, a resounding “revendication of liberty” (26). Chabot’s articulation of sexual and creative liberty with sovereignty is eloquent but far from isolated. Jean-Pierre Sirois-Trahan has recently argued that À tout prendre carved out a cinematic space for a “politics of intimacy” that “foils all the social and political taboos that weigh on the intimate sphere” (20). As a crucial moment in the evolving Jutra myth, these critics celebrate the film’s bold, scandalous, and explicitly sexual qualities as marking a decisive break with the stifling sexual repression of the Grande noirceur. In these readings aligning the Quiet and sexual “revolutions” enable a retrospective reclaiming of Jutra the homosexual as a figure of national liberation. With the 2016 scandal, however, Jutra the pedophile has been summarily rejected, even “abjected,” from the progressive project of Québec national liberation.

The Jutra myth hovers on the cusp of stigma and affirmation that for Heather Love has indelibly marked queer experience and identity:

“On the one hand, it continues to be understood as a form of damaged or compromised activity; on the other hand, the characteristic forms of gay freedom are produced in response to this history. Pride and visibility offer antidotes to shame and the legacy of the closet … Queerness is structured by this central turn, it is both abject and exalted, a mixture of delicious and freak” (2-3).

This account succinctly encapsulates how affectively charged discourses of pride and shame have contributed to the profound contemporary resonance of the Jutra affair. The disgrace of a filmmaker who has been evoked as a mythic and founding figure in the forging of a distinct Québécois national identity and imaginary has led to a scandal of national proportions.

|

|

|

|

| Jutra in McLaren's “Il était une chaise” (A Chairy Tale) (1957). | |