JUMP CUT

A

REVIEW OF CONTEMPORARY MEDIA

![]()

Dreaming in neon.

Brenton Maart, from first solo show, “Temporary Architecture,” PhotoZA, UK.

Brenton Maart: from first solo show, “Temporary Architecture,” PhotoZA, UK.

David Wojnarowicz, a man denied his words.

Black gay men dance with the censor. Frame grab from Video Remains (Alexandra Juhasz, 2005) of the AIDS activist video Tongues Untied (Marlon Riggs, 1989).

Black gay men dance with the censor. Frame grab from Video Remains (Alexandra Juhasz, 2005) of the AIDS activist video Tongues Untied (Marlon Riggs, 1989).

Marcia, Glenda, Juanita and Alex. Friends, activists and collaborators in frame grab from We Care.

The censor strives to silence AIDS education, lived experiences and criticism. She can’t. Frame grab from Video Remains of MPowerment Youth Group.

1999, Becky Trotter, acrylic on canvas, 21" x 15", from Visual AIDS

"Legs up at the Copa Cobana NYC," 1989, Jorge Veras, silver gelatin print, 11" x 14.” From Visual AIDS

A censorship dance. Frame grabs from Video Remains of my earlier AIDS activist video Living With AIDS: Women and AIDS.

A censorship dream. Untitled, 2005, Stephen Andrews, crayon rubbing and mylar, 19" x 24." From Visual AIDS.

AIDS activism, education and community becomes language in my book, AIDS TV, with safer-sex educator Denise Ribble on the cover.

Tom Joslin and Mark Massi in their 1993 Silverlake Life, both died before the video was finished, posthumously, by their student, Peter Friedman.

![]()

AIDS video: to dream and

dance with the censor

“Like the censorship of dreams, the censorship of visual art functions not simply to erase but also to enable representations, it generates limits but also reactions to those limits; it imposes silence even as it provokes responses to silence.”

—Richard Meyer[1] [open endnotes in new window]

This is my provoked response to silence. To begin, I describe a piece of art, Factory Crossword Version 4 (2008), that I saw on a wall at Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions (LACE). I took no notes, so my description comes from the heart. My words prove the lasting hold of vanished images, always to be held in my mind, and now here alive on the page. My words and your reveries are a lasting legacy against silence.

I saw perhaps 15 large-scale photographs in an asymmetrical but grid-like structure networked with lines across a substantial gallery wall. The images were of an abandoned warehouse out there on the edge between the illicit and the familiar. The lines suggested passages I might take through this pictured space. But I also was invited to enter by following the back of a skinny man suggestively clad in leather-bondage garb as he explored the sometimes empty, dripping, and dirty rooms, and as he engaged in sometimes intimate and other times removed interactions with other men, similarly clad. The grey and industrial place felt prohibited: not meant for human habitation, littered with debris and chipping paint. The human interactions felt the same: outside the confines. Here, men were meeting in a place not meant for meeting. Rather, this was a space transformed to address the needs of those who could not do without it. Here, iconographically gay men engaged in social and sexual practices charged by intimacy, vulnerability, and danger. But also familiarity: with this place, each other, and the photographer. Although I have never frequented such a place, I felt comfortable observing it on the wall at LACE, because I am relatively intimate with the lifestyles of gay men, and because the photographer graciously invited me to join him there.

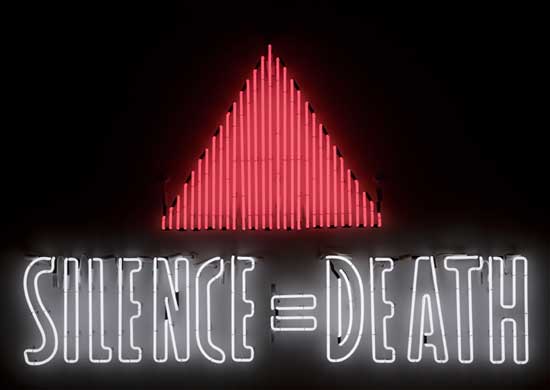

These photographs, by South-African artist, Brenton Maart, a gay man of mixed racial heritage, were commissioned by the Fowler Museum for the MakeArt/Stop AIDS show held at UCLA in 2008. They were subsequently rejected by employees of the Museum, a shocking reverse to the welcome pictured in Maart’s photos. Subsequently extended an invitation to be hung at LACE, I saw them while participating in a panel discussion about their removal from the very show I will discuss in this chapter. Censoring works best when kept a secret; but I will not be silenced, for silence equals death. It says so on the wall of the Make Art/Stop AIDS show. In neon. This now infamous sign by Gran Fury and ACT UP’s (1987) Neon Sign (Silence=Death) from Let the Record Show was remade for this show, moved from shop window in New York to white wall in Los Angeles, where it’s spirit and message were then ungraciously disregarded. I have told you the secret of what was seen and what was lost; now you might choose to dream Maart’s images, keeping them alive. But even so, their vanishing changes this show, how I saw it, what I will say about it, and what its place will be in the history of AIDS art.

Censorship demands an AIDS act; it propels AIDS art. It always has; it still does. Annette Kuhn calls this “the circuit of censorship”[2] and here I will perform the circuit not as series of parties where gay men dance, drink, and hook up, but as another sort of dance through time, one inspired by AIDS videos that spoke strategically to the censor in their own time. I thank the censor for this new framework with which to gaze upon a familiar, tired, and trying history. A sad one. The censor revitalizes me. She teaches me that AIDS video demands censoriousness, dances in response, smirks in disdain, screams in refusal, and misbehaves accordingly. And so will I.

|

|

| Richard Meyer’s Outlaw Representation is an act against the censor. | I still have the button I wore this on. A talisman. |

I thank the censor for forcing me to study censorship. In his book Outlaw Representation: Censorship and Homosexuality in Twentieth-Century American Art, Richard Meyer explains how

“Freud emphasizes the effects of censorship as both repressive and productive.”[3]

Learning of the Fowler’s censorship of Maart’s images felt worse then repression. This was a direct attack on me, my friends, the dead, our history, and the very art movement the museum claimed to support: Silence Equals Death! As days and weeks passed after learning of the loss, I didn’t get less disturbed by time and distance, relaxing into the fact, into their act, saying to myself, “Well, it really is a bold and courageous show, and it’s only one work out of so many.”

No, that’s not how I felt. Instead, I became increasingly angry, mired in a familiar abyss of disavowal, and continually more perplexed: given the many sexually explicit works in the show, why evacuate this innocuous piece? Didn’t they anticipate images of sexuality…gay men’s sexuality? Didn’t they expect transgression? How could this ongoing fear and fantasy about gay men, and queers of color in particular, what Meyer calls “a complex knot of dread and desire”[4] show itself here, today, given our understanding of the silencing of gay men in this particular history, and given the radical designs of this show? And why project this onto children? For, of course, the tired but true rationale for the Museum’s violent act of disappearance was in the name of protecting the innocence of innocents. The predictability of this ritual of avowal and disavowal numbed me. Slowed me down.

How fortuitous, then, that I located a worthy response to this highly scripted dance between righteous gay man and timid straight women on the very wall of their own museum! There spoke a voice from the past, dreaming in his time of a better future sadly not yet arrived. He is no longer able to dance with the censor himself so I perform this function for him. In his 1985 Untitled (One Day This Kid…), David Wojnarowicz scrawls on his childhood photo:

How could they re-enact, re-play this violence, this sacrilege, to that boy, now a dead man, one who they “respect” enough to display in their gallery? How can they enact this violence of silencing on the boys who will come to visit? While censorship is always harmful, the hurt of censorship in relation to AIDS art is formative, primal. This pain is not rational: it’s where we began. I am pulled back to the past, forcefully denied our history and future. I am returned to the closet, unheard, our lives and loves once again unseen, disallowed. We are pulled back to the time when we were forced into action because our friends were sick, in pain, and dying, there was so much we couldn’t say and show, so then, of course, we did: how we put condoms on penises and dental dams on vaginas, how we kissed, who we fucked, how we rioted, who we wanted, how we mourned, how our lives were touched by racism, sexism, and homophobia before during and after AIDS, how once we were polite and then we could no longer be.

|

|

| Videomaker, Marlon Riggs, died of AIDS in 1994. Frame grab from Video Remains of his AIDS activist video Tongues Untied (1989). | Poet Essex Hemphill died of AIDS in 1995. Frame grab from Video Remains of the AIDS activist video Tongues Untied (Marlon Riggs, 1989). |

Meyer notes

“a contradiction that occurs across the modern of censorship: attempts to restrict or regulate sexually explicit images produce their own theater of sexual acts and imagery, their own fantasies of erotic exchange and transgression.”[5]

I set my stage—enraged, a bit timid, but forced to dance—with love, celebration, anger and mourning for the art and artists that were silenced by censors and/or death. And hence, I enact what we most defiantly know about AIDS art and activism: we may not always have the power of institutions or government or funders on our side (although we often do, more on this later), but we carry the influence of cultural capital, the truth of our experience, and the righteousness of our analysis. I may not be a government institution to be fawned to, and I may not be a child to be protected, but I am a scholar, and an activist, and I learned, through AIDS activism and art, the power of my voice when raised with others who see the world and AIDS as do I. So, here I will speak about the history of AIDS video in a new way, and with thanks to the censor, by telling it as a history of strategic acts against her.

|

|

| Early safer sex educator, Denise Ribble, presents a dental dam, from Living with AIDS: Women and AIDS (1987), one of the first AIDS videos about women, made by Jean Carlomusto and me for GMHC’s cable access show. | Aida and her son, Miguel, in a still from We Care: A Video for Careproviders of People Affected by AIDS (1990) which I made with the collective, The Women’s AIDS Video Enterprise of which she was a member. |

|

|

| Not polite; in anger and grief. Frame grabs from Video Remains (Alexandra Juhasz, 2005), ... | ... from the AIDS activist videos Fast Trip Long Drop (Gregg Bordowitz, 1995) ... |

|

|

| ... and Doctors, Liars and Women (Jean Carlomusto, 1988). | Ray Navarro in DIVA TV’s Stop the Church, 1989. A central voice in the AIDS activist video scene in NYC, Ray died in 1990. |

To do so, I will look closely at three video pieces exhibited in the Make Art/Stop AIDS show, as well as some of my own AIDS video and earlier writings about it. I will also relay three censorship stories from my own experience to periodize AIDS activist video history into three acts, three plays with the censor: head on attack, head in the sand, and hearts heavy in our hands. I hope to demonstrate how the changing nature of institutional silencing has insured a variety of strategic responses by video artists. Caught together in our circuit, the censor will ever strive to silence the same things that we are compelled to say: first, our attempts at providing life-saving AIDS education; second, the images of our diverse lived experiences of AIDS; and third, our critiques of the very institutions that disallow our representations and promote our invisibility. Given the omnipresence of the censor, we must ever navigate the extent to which we will be rude, shocking, abrasive, calming, loving, reductive, polite, and transgressive. This, of course, because AIDS mandates that we represent and educate about the oh so complex and controversial issues of sex, sexuality, drugs, activism, poverty, racism, xenophobia, and homophobia. Perhaps polite in many other areas of our lives, we have no choice but to be explicit, outrageous, critical, and courageous when we represent AIDS…which is to dance and dream with the censor.

Period 1: Head on attack

In 1986, I joined a burgeoning movement of artists and intellectuals responding quickly, outrageously, and as activists, to the gruesome and unexpected lived experiences of our friends and fellow NYC inhabitants: primarily gay men, people of color, and urban poor who were infected by and then dying from an unknown disease to the alarming indifference of the media, government, and scientific establishment. I joined ACT UP, began making AIDS video for the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, organized an HIV educational video/support group as my doctoral project, and then wrote a dissertation about it, which would be published by Duke University Press in 1995 as AIDS TV: Identity, Community and Alternative Video.

My AIDS video and scholarly practice from this time demonstrates the first stage of AIDS video: the head on attack. We were exuberant, productive, incouragible. We went with our newly available, hand-held video camcorders to the places that we weren’t supposed to show (much as does Brenton Maart, so many years later, breaking new taboos of exposure). These places were not so new to us. We simply showed where we lived (barrios, art scenes, sex clubs, hospital rooms), and we spoke the critiques of American culture that we often expressed to each other. By making this public through video, even as we had been told, warned, trained, to keep it private, we were forced to invent art practices and activist theories. The censor was everywhere and we rioted and represented in return. In the 1990s, for example, Canadian video artist, activist, and theorist, John Greyson organized two compendiums of AIDS video: AIDS Angry Initiative/Defiant Strategies for Deep Dish Television, and Video Against AIDS, for the Video Data Bank that demonstrate the range of our rage. These and other tapes are archived at the Canadian Vtape as well as the Royal S Marks AIDS Activist Video Collection at the NY Public Library. In the introduction to my book, AIDS TV, I describe AIDS activist video as a player and theorist. Take good note of my stage 1 exuberance, it doesn’t last:

“The production and reception of alternative AIDS TV is a form of direct, immediate, product-oriented activism which brings together committed individuals who insist upon being industrious. No wonder so many alternative AIDS videos have been produced. In the fourteen years since AIDS has known a name, there have been hundreds if not thousands of media productions about the crisis, made by videomakers who work outside of commercial television. Since the mid-eighties, these projects have challenged and politicized the meanings of both AIDS and video. It is the fact of alternative AIDS video that is initially so compelling. Try as I may, I can think of no other social issue that has received this magnitude of attention, in such a brief period, using the form of video production.

Thus, my first task in this study must be to attempt to understand why. Why have there been thousands of AIDS videos produced by artists, community centers, public access stations, ACT UP affinity groups and high school students? These videos document AIDS demonstrations, illustrate how to clean intravenous drug works, interview long-time survivors, depict cunnilingus through a dental dam. Why this form of response instead of or in addition to marching, lobbying or leafleting? What does the fact of the vast alternative AIDS media tell us about AIDS, video and politics? And, for those of us, like myself, who are part of the large and diverse community of makers and viewers: why do I make them? why do I watch them? is there a value to all this video?

The coincidental and not so coincidental lining up of the new video technologies (the camcorder, satellite, VCR and low-cost computer editing), with the AIDS crisis and with theories of postmodern identity politics and multiculturalism are the founding conditions upon which the alternative AIDS media is built. The overwhelming needs to counter the (mis)information about AIDS represented on broadcast television, to represent the under-represented experiences of the crisis, to communicate with others who feel equally unheard, coincide with the formation of a new condition of media practice, the low-end, low-tech video production enabled by new technologies. The possibility of media production for those individuals and communities who could never afford or master it occurred just as there was a social crisis of massive proportions and multiple dimensions that begged to be represented in a manner available to the most and the least economically and culturally privileged. The politics of AIDS—the demands for a better quality of life for the people affected by this epidemic—are well matched by the potentials and politics of video.

This said, I continue to answer the question, “why the alternative AIDS media?” by building upon my frame of coinciding conditions with several more conditions specific to the history of AIDS. Because in its earliest and still most well-known manifestation this retro-virus infected the bodies of white gay men in the United States, this community’s material, educational and creative resources serve as a partial inspiration for the astonishing response to AIDS found in video and television. The artists, critics and “cultural elite” whose deaths were met with cultural indifference or blame in a world which had once seemed to be based upon the security of their dominant race, class and gender, responded in forms with which they were already familiar.[6] Then, there is a body of AIDS theory which suggests that this invisible contagion is the logical culmination of the postmodern condition, only manageable in representation, and best managed in pomo’s definitive discourse, television.[7] There is so much AIDS TV because AIDS and television are so similar: discursive, fleeting, all-powerful. Another motivation for this massive media blitz is the lack of a cure for AIDS, making necessary a focus upon preventative education. Since there is no medium which reaches more Americans (literate or not, English speaking or not) than television, it is the most pervasive and persuasive form for this much needed education.

This is what alternative AIDS TV is about: the use of video production to form a local response to AIDS, to articulate a rebuttal to or revision of the mainstream media’s definitions and representations of AIDS, and to form community around a new identity forced into existence by the fact of AIDS. The process of producing alternative AIDS media is a political act that allows people who need to scream with pain or anger, who want to say “I’m here, I count,” who have internalized sorrow and despair, who have vital information to share about drug protocols, coping strategies, or government inaction, to make their opinions public, and to join with others in this act of resistance. The process of viewing alternative AIDS television—lying on a couch at home watching a VCR, sitting at church, or joined with friends and neighbors at a local screening—is always an invitation to join a politicized community of diverse people who are unified, temporarily and for strategic purposes, to speak back to AIDS, to speak back to a government and society that has mishandled this crisis, and to speak out to each other.”[8]

|

|

| Glenda (center) and her loving family from WAVE: Self Portraits (The Women’s AIDS Video Enterprise, 1990). | Lily Gonzalez, a Latina lesbian with AIDS who is an ex-IV drug-user turned AIDS educator, in A Part of Me (Juanita Mohammed, co-produced with Alisa Lebow 1992), for GMHC’s Living with AIDS Show. |

|

|

| Jean Carlomusto and Gregg Bordowitz discuss video in frame grab from Video Remains of video Fast Trip Long Drop. | Frame Grab from Video Remains of Juanita Mohammed’s Two Men and a Baby (1992). |

AIDS TV was written from my experiences making a community-based, communally-produced AIDS activist video by and for working-class and poor, urban women of color: We Care: A Video for Careproviders of People Affected by AIDS (The Women’s AIDS Video Enterprise—WAVE, 1989). The process, as well as the products, of this project were a major focus of my doctoral research, which became the book I quote from here. What follows is my attempt to describe a video exercise, a self-portrait, produced by Sharon, one of the participants in WAVE. To know her, and her video, is a first step towards understanding the role of the censor in our stage one video practice:

“Tell me about your mother/sister/daughter,” Sharon’s voice queries.

Images of her daughters, sisters, mother answer back, their black faces etched with familial similarities: “If you want my opinion, I’m very proud of her,” says her daughter.

“But what about AIDS?” Sharon wants to know. “Does she devote too much of herself to AIDS, and doesn’t this make you angry at her?”

“Sure it makes me mad when she’s gone so much. But maybe she doesn’t know that, even so, I understand...”

In her self-portrait, these interviews with her family are intercut with Sharon speaking on the beach. I videotaped her one afternoon as she stood on the rocks looking at the ocean. The crashing waves forced me to stand directly in front of her with the Camcorder. In tight close-up the mic mixed her words harmoniously with the ocean’s steady beat. She speaks of the way the ocean purifies her, washes her clean. AIDS’ toll has been enormous on her, bringing the death of countless friends, and the illness and death of more family members than I often have the will to contemplate. She goes to the beach at the Far Rockaways “to get lost:” to lose herself in the breeze, waves and the roar of airplanes taking off; to momentarily lose her memories, her duties; to get the strength to pick up and do it again.[9]

|

|

| Sharon at the Beach from We Care. | Juanita in her bedroom from We Care. |

Sharon’s video is classic stage one: in its power and specificity of voice, speaking forcefully against all that would silence her. Censored until the time of AIDS (by racism, sexism, homophobia and economic disenfranchisement), Sharon demands a voice at this time because she must heal herself and her family. She is compelled to show what has been disallowed to be seen because it is hers. And her video act against the censor introduces my first censorship story. Here’s how I recount it in the book:

“The differing effects of affirmation upon various members of our group provides a telling reminder of our discrepancies in power and privilege. Surely, when We Care does “well” it affects all of us in positive ways, yet only some of the members of the group have resumes where the information that the tape played at The Whitney Museum matter. When a reporter from The Village Voice attended one of our meetings and interviewed everyone afterwards for a story on the WAVE project, we were all excited, proud, nervous—even those of us who didn’t read or care about The Voice. Great, we thought, this is just what we need: public attention, affirmation in a dominant form, we can show our friends, we can show potential funders. When the story took weeks and then months to be written and re-written, and then never ran because of conflict between the writer and her editor, we were reminded of the under side of “real-world” attention: you don’t control it. But more so, it became clear to me that The Voice was not capable of dealing with our kinds of AIDS art production. The Voice did not recognize or respect the tenuous relationship to authority, vulnerability, and expertise felt by these artists: to run the piece would build up authority, to pull the piece was to confirm vulnerability. For the women in WAVE like Sharon—unlike other “artists” who may have more experience with attention, reviews, attention from mainstream institutions—it was a painful, courageous, and distrustful experience to open up to someone from the mass media. When the article didn’t run, everything that we suspected about the dominant culture being uninterested in our story, being manipulative, tricking us, was proven true. The women of WAVE were both hurt and scornful. We gained nothing but pain from this attention from outside where we worked, who we were, what we made. Nevertheless, this experience did not keep us from producing, it simply further entrenched our sense of why our project was unique and deeply important.”[10]

In the Make Art/Stop AIDS show, I believe that the 1990 tape Requiem, by Tracy Rhoades, best embodies the anti-censorship spirit that infused all of our work in this earliest period of activism. As was true for the women of WAVE with the Village Voice, Rhodes literally dances with the censor, refusing her attempts to silence, and instead choreographing the movements that can most efficiently express a sorrow and love that she would deem illicit, making into dance the debris of what is left after the death of his lover. Alone in a black box theater, Rhoades undresses piece by piece, and each item of clothing, left behind after his lover, Jim’s death, unveils a story of Jim’s life. Jim’s abandoned and disrobed clothes serve as witness, the materialization of his ghost, his form devoid of flesh. Converse shoes that reek of his generosity, socks that speak of his self-consciousness, a bloodied sweater that holds traces of a queer-bashing. Speaking from sorrow, emboldened to forgo shame, a dancer who narrates another’s life and then attests to its value through movement, Rhoades will not be that gay boy reduced to suicide and silence. Instead he exorcises the censor and returns his lover through the precision movement of his arms, and his long dance on pointed toe. The videomaking is simple: one take, performer’s body centered. The dance is not.

|

Tracy Rhoades in Requiem, 1990. He died in 1993. Click here to see Requiem, part 1, on YouTube.

|

Especially today, because of course, we know that Rhoades, too ceased to dance, hence:

To

top![]() Print

version

Print

version![]() JC 52

JC 52 ![]() Jump

Cut home

Jump

Cut home

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License.